Unit 2.5: Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Herders

Instructor: Dr. Evan F. Griffith

In Unit 2.5, we will explore traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in the context of pastoralism.

Learning Objectives:

- Define and understand the concept of TEK.

- Explore how herders use TEK for sustainable resource management in rangelands.

- Identify the challenges that threaten TEK in pastoral regions.

- Analyze a Case Study of Turkana TEK in Kenya

Livestream Zoom Session with Dr. Evan Griffith

Topic: Prosopis julifloris: Challenges and Opportunities in East Africa

Date: 29 November 2024

Time: 4 pm Central European Time (9 am Eastern Standard Time)

Zoom ID: 816 3430 9676

Recorded Video: https://youtu.be/NwI91Z4Zatk

Zoom Chat Text | PPT File

2.5.1 Introducing Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Pastoralism

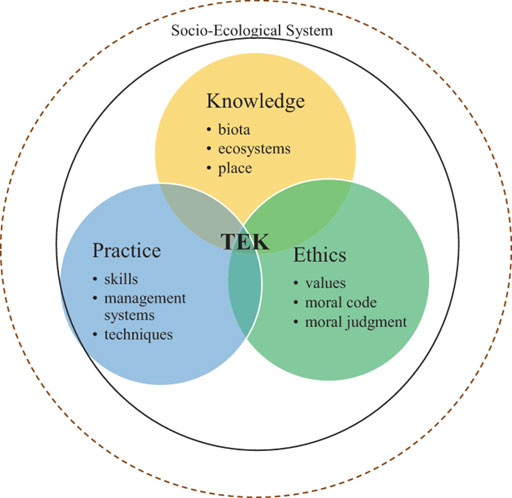

Traditional Ecological Knowledge refers to evolving knowledge acquired by indigenous and local peoples over hundreds or thousands of years through their relationships with the natural world. Core elements of TEK include knowledge (e.g., of biota, ecosystems, and place), practices (e.g., skills, management systems, and techniques), and ethics (e.g., values and moral codes) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Core elements of TEK, adapted from Withanage and Gunathilaka (2022).

Pastoralism, as a livelihood and way of life, can be considered an extension of TEK, developed and adapted in response to rangeland ecosystem dynamics. We will focus on a few aspects of these core TEK areas, including knowledge of fodder and associated management systems, and ethnoveterinary practices. Mobility and transhumance can also be considered types of TEK, which are covered in earlier course sections. Finally, pastoralists' climate adaptation strategies are also grounded in TEK, which we will explore in more detail in the next section.

2.5.2. Pastoral Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Action

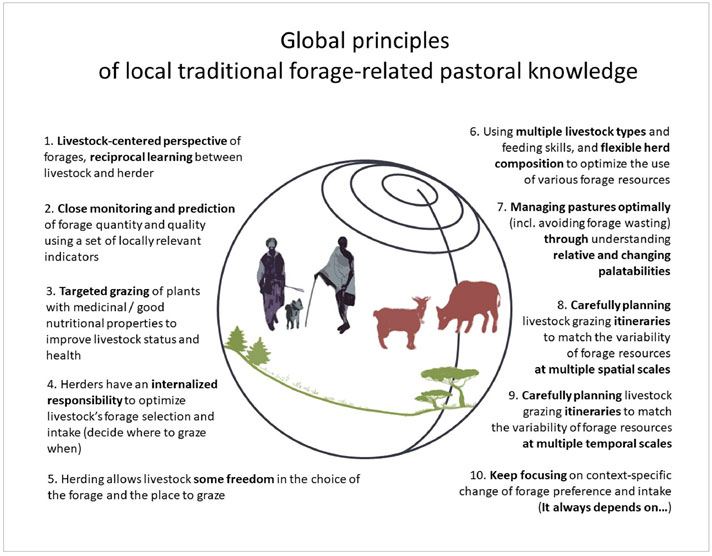

Grazing Behavior: Pastoralists maintain a livestock-centered perspective on forage, engaging in reciprocal learning between livestock and herders. They observe their livestock to assess forage quality and adjust grazing strategies accordingly. This includes general preferences (does the animal like or dislike it), types of livestock (e.g., grazers vs. browsers), what part of the plant is consumed (e.g., leaves or fruits), and grazing behavior (e.g., grazing times – morning vs. evening).

Botanical Features: In addition to animal behavior, herders closely monitor and predict forage quality and quantity using a range of locally relevant indicators. These include nutritional value, seasonal variation, sensitivity to drought and other disturbances, morphological characteristics like sharpness, habitat where forage is found, and chemical content (e.g., salt, vitamins, iron).

Impact on Health: Another critical component of forage is its relationship to livestock health. Herders know what plants are healthy, medicinal, or toxic. They also know what plants cause disease (e.g., refuge for ticks and tsetse flies) or injury and those that improve animal products like milk or fur.

It is worthwhile to briefly consider the differences between intensive livestock production systems and the example of pastoralism use of rangeland resources. In more intensive systems, livestock stay in one location and eat a monoculture diet, often grown offsite and brought to the farm or livestock enclosure. In contrast, pastoralists move across the landscape and take advantage of temporally and spatially variable vegetation based on their intimate knowledge of livestock behavior, plant characteristics, and health effects. These carefully planned “grazing itineraries” are more environmentally sustainable as they utilize a much wider variety of plants and plant products that are available at different times and in different places. Pastoralist herd management practices mimic the movement of wildlife across the rangelands. In a rapidly changing world, we need to consider what pastoralists can teach us about sustainable livestock rearing and management practices – a topic we will return to in the next section focused on climate change adaptation.

Figure 2: Global principles of traditional forage-related knowledge and how they influence herd and pasture management (Sharifian et al., 2023).

Answer the Following Questions in Forum P-001

- Consider Figure 2 and the 10 principles of forage-related knowledge. Choose one of the principles and give a specific example from your own region or county.

- From your experience, how does this knowledge or practice translate to improve livestock health and well-being and support pastoral livelihoods?

Answers and Feedback of Students:

Livestock disease and ethnoveterinary practices: Pastoralists are extremely knowledgeable about livestock disease and how to treat disease in people and livestock using medicinal plants. Understanding the story of rinderpest eradication highlights how important this knowledge is.

Rinderpest, also known as Cattle Plague, arrived in Eritrea in the 1880s from Europe. The resulting epidemic in cattle and cloven-hoofed ungulates swept southward, causing widespread famine and ecological change across the continent. Due to its widespread destruction, rinderpest was targeted for an eradication campaign. However, there were two main challenges to overcome. First, the rinderpest vaccine required refrigeration (i.e., cold chain), which was difficult to implement in endemic areas in Africa. Second, mass vaccination campaigns, the chosen strategy for eradication, failed to reach pastoralist animals in the Horn of Africa (e.g., southern Sudan, Karamoja in Uganda, the Afar region of Ethiopia, etc.) due to the mobility and remoteness of pastoralist communities there. As a result, livestock in these areas acted as disease reservoirs that continued transmission despite mass vaccination campaigns.

Technical and social innovations led to the eventual eradication of rinderpest in 2011. These included a thermostable vaccine developed in 1990, expansion of community-based animal health workers (CAHWs) in vaccination programs, and participatory epidemiology (PE) (Mariner et al., 2012). Participatory epidemiology is the systematic use of methods that empower people to identify and solve their health needs. It encompasses disease investigation, control, surveillance, and descriptive epidemiology (Griffith et al., 2024). Participatory epidemiology is based on the premise that livestock keepers are knowledgeable about livestock disease; i.e., pastoral TEK encompasses health and disease.

Based on this premise, PE methods were used to collect epidemiological information that guided decision-making on rinderpest control options (e.g., targeted vaccination). Livestock owners provided information that led to the identification of several of the final outbreaks of rinderpest, where conventional surveillance activities had failed to disclose the disease. In the later stages of the eradication program, PE helped to confirm the lack of rinderpest cases across Africa.

Definition

Epistemology is the theory of knowledge, especially with regards to its methods, validity, and scope.

Based on the success of PE in contributing to eradicating rinderpest, it has been expanded to other livestock and zoonotic diseases, including PPR, RVF, HPAI, and FMD and recently, human-specific diseases (Griffith et al., 2024). Participatory epidemiology shows the value and importance of combining TEK and Western knowledge, i.e., combining epistemologies or ways of knowing, to combat disease and reach other health and sustainability goals, including climate resilience, which we will explore in the next unit.

Photos Courtesy: Institute for Ethnobotany and Zoopharmacognosy

In addition to general knowledge of disease, pastoralists also have detailed knowledge of plant medicinal properties. This ethnoveterinary/ethnobotanical knowledge is is used by pastoralists worldwide to support human and animal health in the absence of health and veterinary services in pastoral regions (Sharifian et al., 2022). It also reflects a richness in both the cultural history and biodiversity of rangelands.

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

Ethnomedical and ethnoveterinary knowledge is threatened by changing pastoralist livelihoods and priorities of the younger pastoralists. These practices are an important part of cultural and social heritage. They must be part of improving health and well-being in pastoralist communities today, especially in light of insufficient public and private service delivery in pastoral regions.

Traditional ecological knowledge has important implications for livestock management strategies. Next, we will explore a case study of Turkana pastoralists in northern Kenya to understand how ecological knowledge influences livestock management practices.

Analysis Exercise: Case Study 3

Read Chapter 18: Synthesis and Lessons; in Turkana herders of the dry savanna: Ecology and biobehavioral response of nomads to an uncertain environment https://drive.google.com/file/d/1eZhnOD1T-Q69B1MeqccyVtUsarE8n88_/view

Read from page 355 to page 368.

In addition to the pdf link, I have included the following information for your reference:

Figure 3: Vegetation map of Turkana in Northern Kenya

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

2.5.3. Traditional Ecological Knowledge under Threat

Traditional ecological knowledge is essential for improving the functionality of rangeland ecosystems, biological diversity, sustainable management, and social and cultural preservation. It also enhances the resilience and adaptability of pastoral communities. However, TEK relies on knowledge transfer between, for example, elders and younger community members. This knowledge transfer is critical and can be separated into four categories (see Table below).

Table: Types of TEK knowledge transfer. Adapted from Sharifian et al. (2022)

| Type of Knowledge Transfer | Definition |

| Retention | Continuity and persistence of TEK without significant change in its quality and quantity |

| Erosion | Decline or loss of TEK |

| Adaptation | Transformation of TEK to adjust to changes in the environment and local conditions |

| Hybridization | Integration of TEK into another knowledge system |

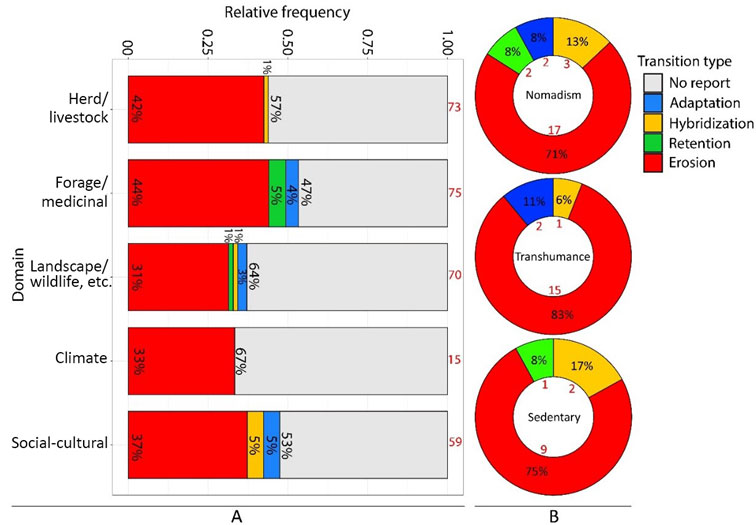

In general, landscape is an expression of variability, pastoralism takes advantage of the variability in potential inputs, which are maximized andDrivers of TEK transition include formal schooling, transition to a market economy, policy and regulations (e.g., land tenure), urbanization, subsistence diversification, environmental and climatic changes, and agricultural expansion, among others. In a recent review, erosion was the most common type of knowledge transfer, specifically regarding herd/livestock and forage/medicine knowledge (Sharifian et al., 2022).

Figure 4 A: Types of TEK transition reported from each major knowledge domain.

Figure 4 B: TEK transitions reported for three pastoral mobility types (Sharifian et al., 2022)

Below, I briefly summarize an example for each type of transition.

Retention: Children of the semi-nomadic Gujjar tribe (buffalo herders) in the high altitudes of the Western Himalayas accompany their fathers and elders to the higher altitudes and help collect wild plants. This shows the retention of TEK among the younger generations (Rana et al., 2019).

Erosion: Among a Maasai community in Narok District, both elders and young people believe that there is a marked decline of traditional medical knowledge (TMK). Elders thought that young people’s prioritization of formal education was to blame, while young people highlighted the lack of opportunities to learn TMK. Land loss and privatization have increased urbanization, which has reduced opportunities to learn about TMK. There is a need to integrate TEK into formal education and community programs (Hedges et al., 2020).

Adaptation: Prosopis juliflora (i.e., prosopis) is an invasive species widespread in semi-arid regions of the world. In Gujarat, India, Rabari pastoralists have adapted to the recent invasion of Prosopis in a variety of ways (Duenn et al., 2017), including:

- Integration of new knowledge – developing new uses of Prosopis including using its leaves and bark for medicinal purposes

- Use of resources – the Rabari use Prosopis for firewood, fending and fodder for livestock (as a last resort).

- Shifting baseline system – older generations view Prosopis as a significant change and problem, while younger generations see it as a normal part of the environment, highlighting an adaptation in the baseline assessment of the ecosystem.

- Coping with environmental changes – the Rabari’s TEK system has evolved to include knowledge of Prosopis’s effect on animal and human health, vegetation, and migration paths.

Hybridization: Young Spanish herders in the Cantabrian Mountains are getting exposed to new sources of training and information, which has resulted in a new understanding regarding scavengers and their role in other nature-based livelihood activities, like nature tourism. Similarly, scientists and policymakers invested in species conservation also gained new insights and knowledge from herders based on their TEK of the importance of scavengers. Integrating TEK and scientific knowledge (i.e., social or co-learning) can benefit biodiversity conservation (Morales-Reyes et al., 2019).

Although knowledge erosion is, at least, the most studied type of knowledge transmission occurring among pastoralists worldwide, hybridization and adaptation are critical in the implication of new solutions to social-ecological challenges in many parts of the world, like climate change.

Watch a Video

Ethnoveterinary practices:

Case Study: Livestock Guarding Dogs (LGDs)

Please read the following case study on livestock guarding dogs: https://lciepub.nina.no/pdf/636097452011012523_Linnell%20NINA%20livestock%20guarding%20dogs_web.pdf

The use of LGDs can be considered a type of TEK, given that these dogs have been an integral part of pastoralism for thousands of years and knowledge is required to train and deploy them most effectively.

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

Wrapping Up the Unit 2.5

A key debate in the literature on TEK is the appropriateness and fairness of using scientific validation measures to assess its legitimacy. Critics argue that scientific validation often excludes relevant, locally legitimate knowledge and disempowers local communities (Tengo et al., 2014). In contrast, the Multiple Evidence Base (MEB) approach values the unique contributions of indigenous, local, and scientific knowledge systems. This approach fosters collaboration, respect, and triangulation to create a comprehensive, legitimate, and inclusive understanding of environmental issues, ultimately improving ecosystem governance (Tengo et al., 2014; see Figure 5). Given how valuable TEK is, given all that we’ve explored in this unit, the MEB approach is especially important for working with pastoralists and addressing health and social-ecological challenges.

Figure 5: The multiple evidence base approach where diverse knowledge systems contribute to generate an enriched picture of a selected problem or issue. Adapted from Tengo et al. (2014).

A few final thoughts before moving to the next unit. Traditional ecological knowledge includes knowledge, practices, and ethics. This unit emphasizes how TEK underlies pastoralism, including herd management strategies and social/cultural practices. Traditional ecological knowledge is under threat from a variety of factors, but hybridization and adaptation show the promise of TEK in contributing to overcoming local and global challenges pastoralists face. In the next unit, we will examine adaptations among pastoralists to climate change.

References Cited:

Duenn, P., Salpeteur, M., & Reyes-García, V. (2017). Rabari shepherds and the

mad tree: the dynamics of local ecological knowledge in the context of Prosopis juliflora invasion in Gujarat, India. Journal of Ethnobiology, 37(3), 561-580. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-37.3.561

Griffith, E. F., Kipkemoi, J. R., Mariner, J. C., Coffin-Schmitt, J., & Whittier, C.

A. (2024). A pilot study expanding participatory epidemiology to explore community perceptions of human and livestock diseases among pastoralists in Turkana County, Kenya. CABI One Health, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1079/cabionehealth.2024.0018

Hedges, K., Kipila, J. O., & Carriedo-Ostos, R. (2020). “There are No Trees

Here”: Understanding Perceived Intergenerational Erosion of Traditional Medicinal Knowledge among Kenyan Purko Maasai in Narok District. Journal of Ethnobiology, 40(4), 535-551. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-40.4.535

Mariner, J. C., House, J. A., Mebus, C. A., Sollod, A. E., Chibeu, D., Jones, B. A.,

... & van’t Klooster, G. G. (2012). Rinderpest eradication: appropriate technology and social innovations. Science, 337(6100), 1309-1312. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1223805

Morales-Reyes, Z., Martín-López, B., Moleón, M., Mateo-Tomás, P., Olea, P. P.,

Arrondo, E., ... & Sánchez-Zapata, J. A. (2019). Shepherds’ local knowledge and scientific data on the scavenging ecosystem service: Insights for conservation. Ambio, 48(1), 48-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29730793/

Rana, D., Bhatt, A., & Lal, B. (2019). Ethnobotanical knowledge among the semi-

pastoral Gujjar tribe in the high altitude (Adhwari’s) of Churah subdivision, district Chamba, Western Himalaya. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 15, 1-21. https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13002-019-0286-3

Sharifian, A., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Wario, H. T., Molnár, Z., & Cabeza, M.

(2022). Dynamics of pastoral traditional ecological knowledge: a global state-of-the-art review. Ecology and Society, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12918-270114

Sharifian, A., Gantuya, B., Wario, H. T., Kotowski, M. A., Barani, H., Manzano,

P., ... & Molnár, Z. (2023). Global principles in local traditional knowledge: A review of forage plant-livestock-herder interactions. Journal of Environmental Management, 328, 116966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116966

Withanage, W. K. N. C., & Lakmali Gunathilaka, M. D. K. (2023). Theoretical

framework and approaches of traditional ecological knowledge. In Traditional ecological knowledge of resource management in Asia (pp. 27-43). Cham: Springer International Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16840-6_3

Further Reading:

Liao, C., Ruelle, M. L., & Kassam, K. A. S. (2016). Indigenous ecological

knowledge as the basis for adaptive environmental management: Evidence from pastoralist communities in the Horn of Africa. Journal of Environmental Management, 182, 70-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.032

Mahdavi, S. K., Shahraki, M., & Sharafatmandrad, M. (2023). The mechanism of

knowledge-based behavior of pastoralists for rangeland management: exploitation, restoration and conservation. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 16296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43590-0

Oba, G. (2012). Harnessing pastoralists' indigenous knowledge for rangeland

management: three African case studies. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 2, 1-25. https://pastoralismjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/2041-7136-2-1