Unit 1.6: Sustainable Livelihood of Shepherds and Pasture Tourism

Instructor: Dr. Muhammad Khurshid

Field Practitioners: Ms. Kuluipa Akmatova

This unit explores the link between pastoral livelihoods and sustainable tourism in pasture regions. Students will learn about the traditional livelihoods of shepherds, including their knowledge of pasture management and animal husbandry. The unit will also discuss the potential of pasture tourism as a means of diversifying income for pastoral communities, promoting conservation, and enhancing cultural exchange.

1.6.1. Pastoral Livelihoods in Sustainability Context

Pastoralists produce food in the world’s harshest environments and pastoral production supports the livelihoods of rural populations on almost half of the world’s land. Arid and semi-arid areas are home to hundreds of millions of pastoralists who depend on livestock (mainly cattle, camels, sheep and goats) for their livelihoods, food security, income and wellbeing.

Students are advised to listen pastoralists views expressed during the Global Pastoralists’ Gathering held in Kiserian Kenya from 9th to 15th December 2013.

Watch the Video

Pastoralism as a sustainable form of livelihood

Video Courtesy: The Water Channel

Now, read thoroughly the text bellow to understand different aspects of pastoral livelihoods.

Pastoralists’ attitudes towards natural resource management are often deeply embedded in their culture and there are many rules governing which resources can be used, when, and by whom. For example, trees are often well protected in pastoral tradition, sometimes for their economic value (for providing shade, fodder, food, medicines etc.) and sometimes without a clear economic rationale. Whether it is rangeland, forest, water, or biodiversity, it is clear that many pastoralists value their natural environment deeply and desire its protection and sustainable management. However, the capacity to manage the environment sustainably for many pastoralists has rested on the capacity of their institutions to make and uphold rules and sanction breach of those rules. These institutions have been weakened in many countries, and even eliminated in some of the former Soviet rangeland countries, and this poses a significant threat to sustainable natural resource management. Many pastoralists have struggled to cope with rapid and large-scale changes in local governance, which has led to damage to their environment. Maintaining, or rebuilding, these systems of governance (which reach far beyond natural resource management) is often another important livelihood goal of pastoralists, and one which may be promoted over the livelihood goals anticipated by development practitioners from non-pastoral societies (IUCN, 2011).

Agro-ecological dynamics play a strong role in shaping pastoral socio-economic livelihood patterns and the related institutional setting, as they are characterized by high variability levels of spatial and seasonal resource endowment and by recurrent risk exposure. Pastoral livelihood systems therefore traditionally account not only for the limited and variable nature of resources, but also for the unpredictability of their supply. Pastoralists build their lives around satisfying the needs of their livestock, following rainfall and fodder over vast distances and across national borders, often covering thousands of kilometers in a single year. As fodder production in pasturelands varies considerably from one year to the next, and from one region to another, herds need to be mobile to adapt to changes in the amount of available vegetation and carrying capacity. Herd diversification allows pastoral communities to cope with the variable and widely-dispersed presence of natural resources in these marginal areas, reducing risk while optimizing productivity. Mobility and divisibility of livestock are important to ensure minimizing risk exposure while optimizing the productivity of available resources. Pastoral mobility requires movement over different scales depending on variable temporal and spatial range production patterns. It depends on the presence of temporarily utilized lands, knowledge of ecosystem productivity potentials (and constraints), and capacities to negotiate or enforce access to these resources. It therefore critically hinges upon technical as well as socio political factors (Nori, 2005).

Knowledge: In-depth pastoral knowledge of complex rangeland agro-ecological dynamics is critical in detecting resource availability to ensure livelihood strategies and coping mechanisms accordingly. This knowledge includes understanding erratic climatic patterns and familiarity with patchy range resources. Water availability is often the limiting factor in pasture utilization, whilst wild fruits and nuts, medicinal plants, and salty areas provide important supplemental food resources for pastoralists.

Access: The political ecology of herding involves social capital and negotiating capacities. Through principles of flexibility and reciprocity, these factors play a critical role in ensuring access to different range resources in times of need, and provide for critical options of dispute resolution during periods of stress and other forms of shock. Accessing resources and services of neighboring communities is therefore a vital element for pastoralists.

1.6.2. Pastoralism as a Risk Management Strategy

Pastoralism has sometimes been described as a risk-averse system, with pastoralists running from one climatic event after another. This description is inadequate, and in contrast pastoralism can be seen as a system that pro-actively manages risk. Many pastoralists seek reliability in highly risky environments: they accept the variability of productive inputs and modify their herding and social systems appropriately. In such uncertain dryland environments, livestock wealth fluctuates greatly: ruined by periodic droughts and recovering with surprising speed in the aftermath, particularly where indigenous breeds are still used. This variability may have merit, considering the extreme variability in primary rangeland productivity: striving for static herd sizes has frequently proven to be environmentally destructive and economically unsustainable. Instead of striving for stability, many pastoralists invest their wealth in social capital, capitalizing on periodic good fortune to ensure that they have long-term insurance through elaborate systems of obligation and reciprocity (IUCN, 2011).

1.6.3. Pastoral Livelihood’s Assets

i. Milk sales and consumption

Animal and milk sales and consumption. The value of animal sales is consistently one of the highest direct values of pastoralism. Milk sales/consumption is an important direct value of pastoralism in developing countries but not in developed economies where the dairy sector is highly intensive and use specialized breeds. In those conditions, milk production from pastoralist systems is less competitive, although it is noted that some industrialized countries maintain a vibrant pastoral dairy sector through the production of niche products, such as organic cheese (e.g. Switzerland and France).

ii. Hides and skins sales and consumption

The sales of hides and skins and its use in the pastoralist production unit is an important direct value of pastoralism. The trade of hides and skins is usually linked to the animals’ sales for meat. In addition, in some pastoral systems, the animals lost to disease can provide skins for processing although the meat is not commercialized, thus creating a bias between the numbers of animal sold and the number of skins produced.

iii. Transport and traction

The cost of transportation is high in pastoral areas and is one of the highest production/transaction costs and a major constraint for market access. The importance of the animals for the livelihood of the owners is significant, although rarely quantified in monetary terms. Livestock provide power for transport and traction for many pastoralists. Ownership of a camel and a cart is a good source of income, sufficient to support a family.

iv. Manure and agricultural productivity

Use of livestock manure is one of the major methods used throughout history to maintain soil fertility and it is still a common practice in many production systems. Manure is a product of pastoralism that could be categorized as a direct value if considered as a final commodity able to be valued using market prices, or as an indirect value if manure is considered as an input needed for some natural processes, e.g. nutrient cycling, or as a production factor for agricultural activities. Manure from different animal species can be collected, kept, dried and sold or used by pastoralists in order to complement their income or contribute to their livelihood.

1.6.4. Pastoral Tourism

There are many products and services that come from pastoral lands or associated with pastoral livelihoods. These include complementary products such as gum Arabic, honey, medicinal plants, wildlife and tourism, ecosystem services (such as biodiversity, nutrient cycling and energy flow) and a range of social and cultural values. One of the greatest values associated with pastoral systems is the tourism value, called as pastoral tourism. Pastoral tourism is increasingly developed in various regions with the aim to promote pastoral cultural and aesthetic landscape values.

Pastoral Tourism offer unique experiences that highlight diverse traditional lifestyles and cultures of pastoralist communities. Pastoral Tourism is one of the leading sectors in foreign exchange earnings and employment. Pastoral tourism is a new tourism niche, very much related to agritourism, cultural tourism, educational tourism, and sustainable tourism due to its numerous implications involving the attitude of both farmers/shepherds and of tourists.

The key activities across all the Pastoral Tourism include the following:

- Homestays: Staying with local families to gain firsthand experience of their daily lives and routines.

- Traditional Crafts: Learning and participating in the creation of traditional crafts, such as beadwork, pottery, and weaving.

- Rituals and Ceremonies: Observing or participating in important cultural rituals and ceremonies, including coming-of-age ceremonies, weddings, and festivals.

- Sustainable Practices: Learning about traditional and modern sustainable practices pastoralism, including water conservation, land management, and livestock rearing.

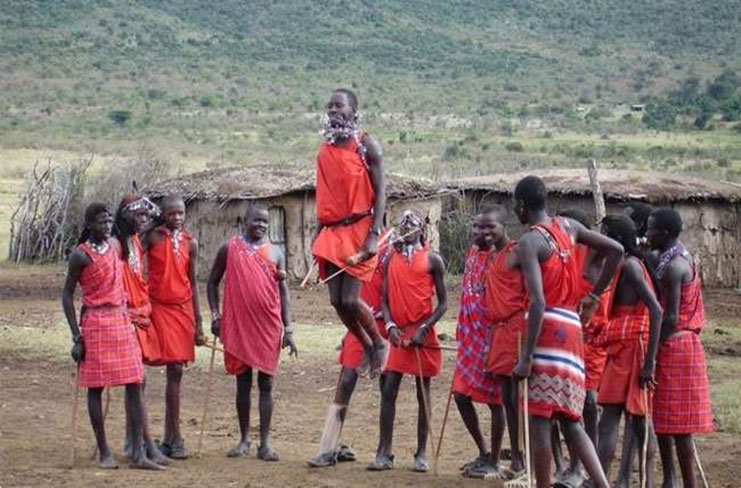

Photo: Massai people showing their traditional culture (Picture courtesy: Great Adventure https://www.greatadventuresafaris.com/experience-the-masai-people-culture-in-masai-mara/)

Photo: Kalash people in Chitral Valley (Pakistan), performing traditional dance (Picture courtesy: https://www.apricottours.pk/tours/kalash-festival/)

Case Study from Rural Development Fund, Kyrgyzstan: Unlocking Chychkan’s Mysteries: Nature, History, and Traditional Wisdom

Students are advised to download the RDF Case Study document from the link and read it thoroughly. Based on the case study, the students need to answer the questions of the quiz.

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

Livestream Zoom Session by Field Practitioner Ms. Kuluipa Akmatova

Topic: Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity

Date: 23 November 2024

Time: 2 pm Central European Time (CET)

Zoom: 842 4779 2697

Recorded Video: https://youtu.be/rnVxcbz7u3U

Zoom Chat Text | PPT File

References Cited:

Davies, J. and Hatfield, R., 2006. Global Review of the Economics of Pastoralism. The

World Initiative for Sustainable Pastoralism. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). https://agritrop.cirad.fr/549237/1/document_549237.pdf

IUCN (2011). Supporting Sustainable Pastoral Livelihoods: A Global Perspective on

Minimum Standards and Good Practices. Second Edition March 2012. Nairobi, Kenya: IUCN ESARO office. https://www.iyrp.info/sites/iyrp.org/files/IUCN%20Pastoralism%20manual_for_min_standards_may_2012.pdf

Nori, M., Switzer, J., & Crawford, A. (2005). Herding on the brink: Towards a global

survey of pastoral communities and conflict. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/security_herding_on_brink.pdf

Rongna, A. and Sun, J., 2020. Integration and sustainability of tourism and traditional

livelihood: A rhythmanalysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(3), pp.455-474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1681437