Unit 1.5: Natural Livestock Farming and Grazing Management

Instructor: Dr. Muhammad Khurshid

Focusing on sustainable livestock farming practices, this unit teaches you about the principles and techniques of natural livestock farming and grazing management. Topics include rotational grazing, pasture rest periods, and the integration of livestock with crop production. Students will learn how to manage grazing to maintain pasture health, improve soil fertility, and reduce the environmental impact of livestock farming.

1.5.1. Natural Livestock Farming

Understanding Natural Livestock Farming

Please read the following points:

- Natural livestock farming is an approach that focuses on raising animals in ways that align with their natural behaviors and the surrounding environment, emphasizing sustainability and health. This method prioritizes organic, chemical-free practices, reduced use of antibiotics, and maintaining animal welfare by allowing them to graze freely and live in stress free conditions in natural habitats. It deliberately avoids the use of synthetic inputs such as drugs, feed additives and genetically engineered breeding inputs. This natural livestock farming is also called organic livestock farming

- Agrochemicals, veterinary drugs, antibiotics and improved feeds can increase the food supply while minimizing production costs in various livestock production systems around the world. However, these days, quality-conscious consumers are increasingly seeking environmentally safe, chemical-residue free healthy foods, along with product traceability and a high standard of animal welfare. Livestock producers may provide these quality products through adoption of conventional organic practices (Chander et al., 2011).

- Under organic livestock production systems or in other words Natural Farming, consumers expect organic milk, meat, poultry, eggs, leather products, etc. to come from farms that have been inspected to verify that they meet rigorous standards, which mandate the use of organic feed, prohibit the use of prophylactic antibiotics (though in fact all antibiotics are discouraged except in medical emergencies) and give animals access to the outdoors, fresh air and sunlight.

- Production methods are based on criteria that meet all health regulations, work in harmony with the environment, build biological diversity and foster healthy soil and growing conditions. Animals are marketed as having been raised without the use of persistent toxic pesticides, antibiotics or parasiticides. Animal health and well-being through better living conditions, improved welfare measures and good feeding practices are ensured through a set of standards and the maintenance of written records by organic livestock farmers. Better management practices and prevention of illness are emphasized over treatment (Von and Sørensen, 2004).

Key Characteristics of Natural Livestock Farming

The primary characteristics of natural livestock production systems are:

- well-defined standards and practices which can be verified

- greater attention to animal welfare

- no routine use of growth promoters, animal offal, prophylactic antibiotics or any other additives

- at least 80 percent of the animal feed grown according to organic standards, without the use of artificial fertilizers or pesticides on crops or grass.

Key Consideration of Natural Farming

Some key considerations in natural animal husbandry that producers and other stakeholders need to take into account are listed below:

| 1 | Animal welfare | Ensuring animals live in environments that allow them to express natural behaviors, such as grazing, roaming, and socializing in a stress-free setting. |

| 2 | Sustainable Grazing Practices | Using rotational grazing to maintain pasture health, reduce soil erosion, and enhance biodiversity in rangelands or pastures. |

| 3 | Livestock Feed | Providing animals with organic feed that is free of synthetic chemicals, ensuring that their diet is natural and produced organically. This includes pasture, forage and crops. |

| 4 | Minimal Use of Antibiotics and Chemicals | Avoiding the routine use of antibiotics, hormones, and synthetic chemicals to treat animals, focusing instead on preventative care and natural treatments. |

| 5 | Living conditions | An organic livestock producer must create and maintain living conditions that promote the health and accommodate the natural behavior of the animal. These living conditions must include access to the outdoors, shade, shelter, fresh air, direct sunlight suitable for the particular species and access to pastures for ruminants. |

| 6 | Integrated Farming Systems | Combining crop and livestock farming to create synergies between plant and animal production, such as using manure as a natural fertilizer |

| 7 | Waste management | Organic livestock producers are mandated to manage manure so that it does not contribute to the contamination of crops, soil or water and optimizes the recycling of nutrients. |

1.5.2 Animal Health Care

Natural livestock production requires producers to establish preventive health care practices. These practices include:

- Selecting the appropriate type and species of livestock

- Providing adequate feed, creating an appropriate environment that minimizes stress, disease and parasites

- Administering vaccines and veterinary biologics

- Following animal husbandry practices to promote animal well-being in a manner that minimizes pain and stress.

Photo: Livestock grazing on lush green pastures with fresh grasses, producing high quality and tasty products, having much higher nutritional contents (Courtesy: The Cattle Site)

Producers cannot provide preventive antibiotics. Producers are encouraged to treat animals with appropriate protocols, including antibiotics and other conventional medicines when needed, but these treated animals cannot be sold or labelled as organic. Producers cannot administer hormones or other drugs for growth promotion.

1.5.3 Grazing Management

Grazing management broadly speaking is the manipulation of grazing animals to achieve desired results. These results generally include maintenance or improvement of range productivity, efficient utilization of the forage resource and production of animal products from livestock (Nigus, 2017). Grazing management is the care and use of range and pasture to obtain the highest sustainable yield of animal products without endangering forage plants, soil, water resources and other important land attributes. A grazing system is a plan for managing when and where livestock graze. It is a strategy for making productive use of pasture resources so that livestock production goals can be met while maintaining and improving the pasture.

Good grazing management should:

- Keep pasture covered with desirable and healthy forage plants.

- Support the increase or maintenance of livestock production capacity and wildlife habitat.

- Improve water-holding capacity of the land base and prevent rapid runoff of rainfall.

- Control soil erosion.

- Balance forage supply with livestock production.

Benefits of good grazing:

- Removes older plant material that is less vigorous.

- Increases light available to lower, younger leaves.

- Improves water conservation.

- Recycles nutrients through manure and urine.

Poorly managed pasture land means rainfall and snowmelt will run off because:

- There is not enough vegetative cover to slow water flow.

- There is less organic matter in the soil to absorb water.

- Compaction from trampling further reduces water infiltration.

- The increased runoff can cause soil erosion and reduce moisture needed for re-growth.

Stocking Rates

For optimum pasture use, there must be enough animals to use the forage produced; it must achieve the appropriate animal performance and leave the desired amount of carryover or stockpiled material. The stocking rate or carrying capacity is the number of animal units grazed on the pasture for the season. Carrying capacity is the potential stocking rate of a given parcel of land. If the range is in good to excellent condition, the stocking rate and the carrying capacity may be the same, but if it is a dry year, or if the range is in fair to poor condition, the stocking rate must be reduced to allow for recovery. Carrying capacity and stocking rate are measured by animal unit month (AUM), which is the amount of pasture needed to support a 1,000 lb. cow (with or without a calf) for one month.

Stocking Density

Stocking density refers to the number of animal units grazing one acre for one day. It is measured as the combined weight of the grazing herd per unit of grazing area for one day. Low stocking density can result in uneven use of the pasture; high stocking density can cause damage to sensitive grazing areas, but may be used as a tool to improve pasture productivity.

Carryover

Carryover is the amount of forage left when grazing ends. It protects the soil surface from the drying effects of direct sunlight and wind, and leaves enough leaf area for plant regrowth.

1.5.4 Rotational Grazing: Best Management Practice

- When one portion of the pasture is grazed at a time while the remainder of the pasture “rests.”

- Pastures are sub-divided into smaller areas (called paddocks) and livestock are moved from one paddock to another.

- Animals are introduced to new feed in a new paddock on a “frequent” basis.

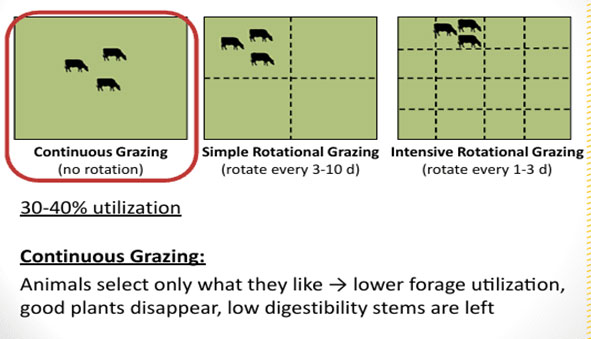

Diagram Courtesy: Dr. Amanda Grev, Orange Specialist, University of Maryland Extension

Four Principles of Pasture Management

Rotational grazing puts into practice the four principles of pasture management.

| 1 | Balance the number of animals with available forage supply. |

| 2 | Manage livestock distribution effectively. |

| 3 | Balance periods of grazing with sufficient periods of effective rest to manage and maintain the vegetation. |

| 4 | Avoid grazing during sensitive periods. is includes times when elds are flooded, soils are saturated, drought conditions prevail, and during wildlife nesting. |

Types of Rotational Grazing Systems

There are different types of rotational grazing systems that could be incorporated into a livestock operation. They include strip grazing, forward grazing, mixed grazing, Intensive Rotational Grazing.

i. Strip Grazing

The animals will receive enough pasture supply to sustain grazing from several hours to a couple of days depending on the forage species by utilizing movable electric fences. It is important that when using strip grazing animals start grazing close to the water source to avoid trampling of the forage when returning to the water source. This grazing method is labor intensive because electrical fences have to be moved frequently, but it results in the utilization of high-quality feed with the least waste and damage to a pasture.

ii. Forward Grazing

The pasture is grazed by two groups of animals within the same species. Usually, young animals or animals with higher nutritional needs are allowed to graze the top of the plants first with the most nutritional leaves. The second group of animals then will graze the forage left by the first group. This is a situation where calves might be grazing before cows. This method could give an advantage to higher weaning weights when forage production might be limited or where competition for forage might exist. Forward grazing is usually accomplished by using creep gates or by setting fences high enough for the young animal to pass underneath.

iii. Mixed Grazing

Common method practiced by producers that might have different types of livestock (e.g. horses, cattle, sheep, or goat) in the grazing at the same time in the same pasture. This type of management offers the opportunity to graze plants more evenly since one type of livestock might graze plants not grazed by the other group. Usually, sheep and cattle are an ideal combination for this type of grazing system. It is not recommended to graze sheep and horses together since they are considered non-selective animals and could affect forage production and persistence of favorable species.

iv. Intensive Rotational Grazing

A rotational grazing system gaining a lot of interest and it requires the pasture being divided into numerous paddocks, enabling hourly to daily animal rotation among paddocks. This type of system is also known as MIG. High stocking rates can be grazed in the paddocks until the forage is grazed down evenly and closely. Stocking density could range from 100 to 400 heads/acre depending on the management of the operation. This management system emphasizes more management of forage consumption, quality, and re-growth. Paddocks are grazed on the basis of growth and quality, but not always in the same order.

1.5.5 Continuous Grazing and Overgrazing

Continuous grazing is usually defined as putting a set of animals out on a pasture and leaving them in the same pasture year-round. Continuous grazing usually leads to the overgrazing of specific areas due livestock selectivity and causing issues with fertility and weed control. Under continuous grazing, the number of animals that could graze a specific area should be determined by the available forage yield during the lowest pasture production; usually from July to October depending on the area of the state. Some of the drawbacks that could seeing with this grazing system include low animal gain per acre, waste of forage biomass and quality, and selective grazing cause the pasture to become less productive with time and the loss of desirable species. This Continues grazing leads to “Overgrazing”.

Overgrazing

Overgrazing occurs when livestock or wildlife feed excessively on vegetation in a particular area, resulting in the degradation of the land. This process leads to the depletion of plant cover, soil erosion, reduced biodiversity, and, eventually, the desertification of the land. Overgrazing is a significant concern in pastoral regions, especially in arid and semi-arid environments, where vegetation recovery is slow due to limited rainfall.

Indicators of Overgrazing

- Top soil exposed and productive vegetation removed

- Toxic weeds or unpalatable plants species encroached the pastures and palatable species (plants) disappeared or overused by livestock

- Increased runoff and soil erosion

Photo: Degraded or overgrazed pasture in Northern Pakistan, Weeds encroachment on the pastures (Photo by Muhammad Khurshid, 2022)

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

References Cited:

Chander, M., Bodapati, S., Mukherjee, R. and Kumar, S., 2011. Organic livestock

production: an emerging opportunity with new challenges for producers in tropical countries. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 30(3), pp.569-583. http://dx.doi.org/10.20506/rst.30.3.2092

Nigus, A., 2017. Pasture management and improvement strategies in Ethiopia. Journal of

Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 7(1), pp.69-78. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3359722

Von Borell, E. and Sørensen, J.T., 2004. Organic livestock production in Europe: aims,

rules and trends with special emphasis on animal health and welfare. Livestock Production Science, 90(1), pp.3-9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301622604001150

Further Reading Material:

Vallentine, J. F. (2000). Grazing management. Elsevier. https://shorturl.at/g4Cq3

Von Borell E. & Sørensen J.T. (2004). – Organic livestock production in Europe: aims,

rules and trends with special emphasis on animal health and welfare. Livest. Prod. Sci., 90(1): 3–9. https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/24248/7/24248.pdf