Unit 3.1: Problems and Issues Challenging the Rangelands and pastoralism

Instructor: Dr. Hasrat Arjjumend

In this Unit 3.1, we will understand the problems and issues challenging the rangelands in general and in case study contexts.

3.1.1 Participatory Exercise in Forum P-001

The exercise that students are supposed to do is function within the boundaries of ‘commons’ or common land perspectives. So, before jumping to exercise, let us recapture that:

“Common land is owned collectively by a number of persons, or by one person with others holding certain traditional rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect firewood, or to cut turf for fuel. A person who has a right in or over common land jointly with others is called a commoner. Originally in medieval England, the common was an integral part of the manor and, thus, part of the estate held by the lord of the manor under a feudal grant from the Crown or a superior peer, who in turn held his land from the Crown, which owned all land. This manorial system, founded on feudalism, granted rights of land use to different classes. The ownership of rights belonged to tenancies of particular plots of land held within a manor. A commoner would be the person who for the time being occupied a particular plot of land. Some rights of common were said to be in gross, or unconnected with tenure of land.”

Task and Instruction for Students

To understand the problems and issues that challenge the rangelands and pastoralism, all the students are advised to enter Forums and click topic P-001. There, every student is supposed to write at least one problem or issue being faced by pastoralists in his/her country or region. Do not stick to climate change only. Climate change is one problem; but there are other two dozen of critical problems.

Task for Instructor/Facilitator

Instructor/Facilitator will closely follow the activity of students in the Forum P-001. The problems or issues suggested or highlighted by students will not only be responded and cross-discussed right in the Forum, but also be taken to be listed in this section.

Some of the problems and issues are flagged hereunder for further readings and discourse:

- Subjugation of pastoralists by state policies,

- Civilized ideology encourages the sedentarization,

- Military pacification and political control, and

- Recent phenomenon of globalization.

- Borders closed for lansdcapes and grassland ecosytems

- Hostile attitude of governments to pastoralism

- Marginalization, Social Exclusion and Disenfranchisement

- Non-Recognition of Customary Land Rights

- Violation of Existing Policies and Laws on Pasturelands

- Fragmentation of Rangeland Habitats and Disturbed Migratory Routes

- Massive Conversion of Rangelands to Industrial/Urban Uses

- Enclosure of Common Lands, incl. forests, meadows, parks

- Encroachment of Pasturelands by powerful elites, mining, factories, government departments, politicians, etc.

- Breakdown of Traditional Village Institutions protecting the commons e.g. Oran, Gochar, Bilanaam

- Atrocities, Exploitation, Prosecution of Nomads by Police

- Changing Weathers and Increasing Uncertainties

- Increased Veterinary Diseases and Lack of Animal Care

- Changing Occupations and Declining Population of Herders (Invisibility, Unrepresentation, Deliberate Exclusion)

Photo Courtesy: Javi921, Pixabay.com

3.1.2 Exclusion of Nomadic Pastoralists and Policy Asymmetry

Before we move to the next Unit 3.2, let us understand the phenomenon of exclusion withy special reference to the nomadic pastoralists.

Read the Bare Fact

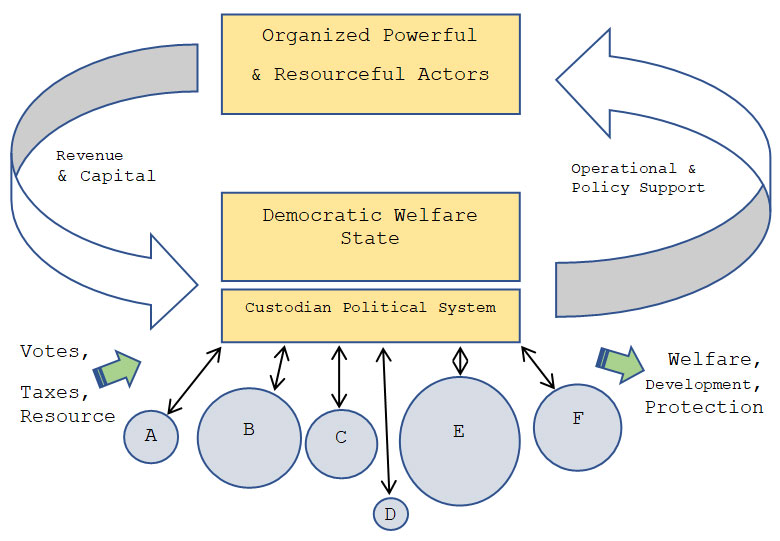

Let alone the autocratic systems, the democratic States also function in the larger interests of haves and powerful economic/social groups. Undeniably, a State is formed from acquiring public resources. The political system, custodian of State, needs resources and revenues required to acquire political dominance in a democracy, particularly. Although the political dominance (through elected majority) comes from the votes of haves not and weaker constituencies, yet the political system works chiefly for the vested interests of haves and powerful groups simply because the largest share of revenue comes from those organized actors (refer to the diagrammatic expression in Figure 3.1). However, certain social or economic groups organize themselves, get mobilized, and assert to influence the policy/law making institutions. But, the marginalized, weak and less-represented social groups, who are not organized and have least/fragmented voting power, are excluded or disenfranchised in the political and policy processes (Arjjumend, 2024). This phenomenon needs to be examined explicitly in particular case of mobile pastoralist groups.

Photo courtesy: Ivana Tomášková, Pixabay

The nomadic people have faced and been facing gross marginalization, deprivation, discrimination, dispossession and criminalization. Policy and law making process at international, regional and national levels has ever neglected and excluded mobile pastoralists, synonymous to Roma people in Europe. Wherever the grazing commons are included in agriculture or rangeland policies, still an “inequality” sounds high. Policy making process in pastoral development continues to be hampered by 1) the dominance by mainstream commercial groups, 2) prevalent biases, and 3) knowledge barriers. The figure 3.1 depicts that the powerful commercial lobbies having economic interests in rangeland resources (demanding for their projects like mining, tourism, ranching, hydropower, forestry, agriculture, etc.) have not only influenced the policy making institutions but also have occupied entire policy & legal space, mostly in their favour (Arjjumend, 2024).

The livelihoods of pastoralists depend on the grazing commons (rangelands) through their livestock grazing. But, commercial demands of rangelands triggered its land use change, being privatized, converted to cultivated lands, reserved for nature conservation, leased for mining and oil extraction, used for governments’ mega-projects, or made inaccessible through artificial enclosures. Additionally, rangeland resources are restricted or circumvented for the grazing activities of pastoralist herders. The following “inequalities in policy processes” in context of mobile pastoralist communities worldwide are observed (Arjjumend, 2024):

- Disenfranchising and depriving the weak and economically poor;

- Subscribing the deep ecologists and green missionaries who portray pastoralism as enemy of ecology (inherent enclosure paradigm);

- States responding to market and powerful commercial lobbies demanding rangeland resources (grasslands, meadows, ranches, forests, etc.);

- Competing commercial lobbies are stronger with massive inputs of capital and power, and they succeed in acquiring common lands for industrial agriculture, mining, energy projects, tourism, oil & gas exploration, etc.;

- Most of the policies tend to be against mobile pastoralists’ existence, coupled with infringement of pastoralists’ customary rights and enclosure of grazing commons;

- Whereas many politically active communities bargain and assert for their rights’ inclusion in policy processes, the mobile pastoralist groups still remain marginalized and alienated from the inclusion;

- Lack of organization/institutionalization, poor mobilization and weak representation of mobile pastoralists are responsible for their persisting exclusion;

- Least population size and demographic decline among the pastoralist communities lead to their insignificant voting power (with lack of negotiation);

- Unequal laws and policy making brings about disastrous effects not only on the affected people but also on the Earth’s resources and countries’ development.

Above analysis elucidates that the policy and legal space is filled by the powerful actors who not only push behind the weak and excluded groups from policy considerations but also succeed in grabbing and controlling the commons or public resources (Arjjumend, 2024).

Read the Two Parallels

Exclusion and Criminalization Stories of Roma People

“Europeans and Americans often refer to Roma with the derogatory slur “Gypsies.” Europeans enslaved Roma until the 1800s and conducted genocides of Roma throughout Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 20th century, Hitler and his Nazi supporters carried out the ethnic cleansing of 250,000 Romani people during the Holocaust. Today, European governments subject Roma to disproportionate imprisonment, police brutality, housing discrimination, and legalized segregation efforts. I’ve heard European people my age, upon finding out I was Romani, shamelessly voice their disdain for ‘dirty’ and ‘thieving Gypsies’—the racism is simply that blatant. Likewise, the average American is constantly consuming media like the TV show “My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding” or the Disney film Esmeralda, solidifying the vision of Roma as exotic, mysterious, or seductive. In the United States today, there are over one million Roma, many of whom keep their Romani identity private in order to avoid the kind of racism that Roma face in Europe. However, American Roma still face a lot of the same forms of persecution and racism that they have faced throughout Europe, specifically as targets of policing.” (Source: Charlotte Haq)

India Government’s Renke Commission (20028) Report

“Most of the Denotified and nomadic community members face abuse of human rights by the law enforcing authorities, realtors, politicians, landlords, and the village communities. They are exploited every one of them. They are many a time victims of the misuse of power by the police and the caste communities in the villages. They are arrested or illegally confined for any theft or burglary indulged in by others. To put it differently, if the fence eats the crop who can save the crop and whom can the crop complain? If the State, which is supposed to look after the welfare of its citizens, becomes the tormentor, who can rescue its subjects and to whom can they look up to for help.” (Source: G.B. Mukherji)

Wrap Up the Unit 3.1: Make Notes and Post in Forum P-001

- In your short note, please highlight what new thing you have learnt from lesson written above in Unit 3.1?

- Have you observed any exclusion and marginalization process targeting pastoralist people in your area or region? Explain in short.

Answers and Feedback of Students:

M3 Responses Students1

Essential Further Readings

Arjjumend, H. (2024). Rangelands and Pastoralism in Globalized Economies: Policy

Paralysis and Legal Requisites. Pastures & Pastoralism, 02, 34-48. https://doi.org/10.33002/pp0203

Haq, Charlotte (2022). Romani Banditry: Understanding 'criminal' Roma

pickpocketing practices. The Indy. https://shorturl.at/t8tKn

Mukherjii, G.B. (2015). Fading Lifestyles, Shrinking Commons. Foundation for

Ecological Secirty, Anand, Gujarat, India. https://rln.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/fading-lifestyle-shrinking-commons.pdf

Schlager, E. (2001). The Plight of the Roma in Eastern Europe: Free At Last? Meeting

Report #226, Global Europe Program, Wilson Centre, Washington, DC, USA. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/226-the-plight-the-roma-eastern-europe-free-last

Optional Further Reading

Babken Babajanian and Jessica Hagen-Zanker (2012). Social protection and social exclusion: an analytical framework to assess the links. ODI Working Paper, Overseas Development Institute, UK. Download PDF