Unit 1.2: Pastures and Pastoralists Communities (Case Studies)

Instructor: Dr. Muhammad Khurshid

Recap of the Previous Unit:

Brainstorming [randomly asked some questions related to previous contents]. Following to this activity, start new Unit of this module. Unit 1.1 (Pastures and Rangelands) of this module successfully completed, now we are going to start second Unit 1.2 (Pastures and Pastoralists). Particularly, in this unit we will try to familiarizing you with the historical and cultural contents of pastoralists and their deep connection with their environment like how they manage and sustain their pasturelands.

This Unit 1.2 examines the relationship between pastures and pastoralist communities through various case studies from different regions. You will explore the cultural, economic, and social dimensions of pastoralism, understanding how pastoralist communities manage and interact with their environments. The case studies will highlight both the challenges and the adaptive strategies employed by these communities to maintain their livelihoods in changing environmental conditions. The unit will also discuss into the conflicts and synergies between pastoralists and other land users.

Expected Outcomes:

By the end of this Unit, the students will learn:

- The herding way of pastoralists on pastures use pattern

- Centuries-old cultural features of pastoral communities

- Examples (case studies) of pastoral way of life, and herding pattern

- Challenges faced by pastoral communities

Photo Credit: Kelley Lynch/USAID

1.2.1. Pastoralism or Pastoral System

Pastoralism is a historically resilient livelihood strategy that is often practiced in various pastoral regions that are too poor to support crop agriculture. Pastoralists are the people who sustain pastoralism for their livelihoods, pastoralists herd livestock in rural and peri-urban areas where access to natural resources, namely water and grazing land, is limited. Pastoralists, often characterized as mobile and with limited access to markets and social services, and social networks (Little, 2015). Pastoralism one of the oldest human ways of life, centered around animal husbandry on natural pastures in the drylands, the tropics, at high altitude and high latitude. There are between 22 and 500 million pastoralists globally who subsist by raising flocks of diverse ruminants and camelids on open and communal rangelands that require mobility ranging from nomadic to transhumance to limited rotation. Globally, around 1.3 billion people benefit economically from the value chain. Besides the millions of pastoralists worldwide, pastoralism uses more than half of the planet’s agriculture land and 69% of its drylands.

Pastoralists are agriculturalists who keep domesticated livestock on natural pastures and depend upon their animals as their primary source of income. Traditionally, pastoral land rights consisted of access to the key natural resources required to sustain mobile livestock production — pastures, watering points, and the movement corridors that linked together seasonal grazing areas, pastoral settlements or encampments, and markets. However, pastoralists and their property rights have been in retreat for several centuries. Pastoralists employ a diverse set of animal management strategies to ensure their subsistence and that of their herds. One important husbandry practice involves moving livestock to different pastures in order provide herd animals with a continuous source of fresh graze. The spatial extent of pasturing systems and the intensity of pasture use depend on a complex intersect of ecological and social factors including seasonality, graze availability, water point, predators, stocking rate, and pasture access rights. Typically, contemporary pastoralists partition their herd animals into different groups depending on species, age, and animal value. These separate herds are then directed to different pastures according to the quantity and quality of pasturage in order to balance graze intake and (re)productive output. The practice of partitioning herds and subsequent dispersal of animals to different pastures is widely practiced in pastoralist societies across the globe (Dong et al., 2016).

Photo Courtesy: International Land Coalition (ILC)

1.2.2 Case Study: Pasturing System in Kazakhstan

“Pastoralists in Kazakhstan also employ several variants of this herd management strategy, taking advantage of diverse forage quality and quantity on the landscape, both of which vary on a seasonal basis. These include intensive pasturing strategies involving grazing of herds (cattle, goats) within 5 km of small villages and more extensive herding strategies that place herds onto distant pastures up to 20 km from settled areas (horse, cattle, sheep goat). Some herders graze livestock at distant pastures more than 20 km from village while others entrust their livestock to owners of remote pastures. Pasture stocking rates (density of animals grazing per acre) vary depending on local environmental conditions that in turn influence the spatial extent of pasturing systems. For example, locations that receive higher amounts of precipitation, which promotes pasture growth tend to support high herd densities even for heavily subscribed pastures located near villages. Kazakh pastoralists also divide small-stock and large-stock into separate pastures. Cattle are frequently grazed on low-quality forage (e.g., coarse reeds) in river floodplains and saline marshes located within 5 to 20 km villages. During the milking season, lactating cows and suckling calves are often grazed on higher-quality pastures located near villages. Sheep and goats are often grazed in the open steppe where they feed on shorter herbs and finer grasses that can be grazed all year. While all livestock roam somewhat freely, horses are the most autonomous and least likely to be attacked by predators; therefore, they range the farthest from villages searching for appropriate vegetation” (Ventresca et al., 2019).

1.2.3 A Case of Pastoralists from Himalayan Region

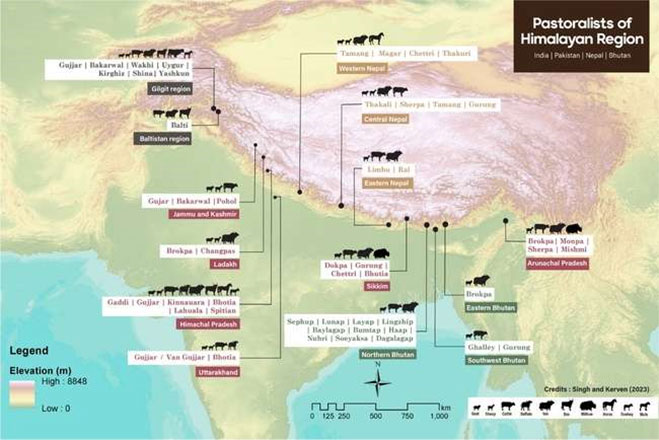

Pastoral tribes in Himalayan region (Himalayan covers political boundaries of Pakistan, Indian, Bhutan, Nepal and Tibet Autonomous Region of China, that is a hot spot of pastoralists’ communities including the nomadic, transhumant and agro-pastoralists across the region (Kreutzmann, 2012).

Photo: Pastoralists of the Himalayan region across India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan. Map credits: Gauri Dangol (Design credit: Gurpreet Kaur Sokhi)

Pastoralist Way of Life in Himalaya

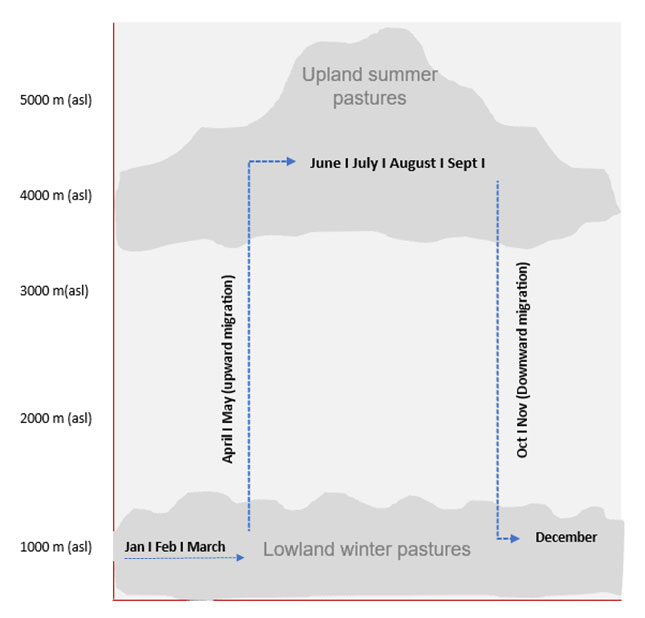

Pastoralists in the Himalayan pastoral areas have adopted a nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyle, migrating between summer and winter pastures. They are keeping large herds, comprised of sheep, goats, Yaks and equines. In the summer they move to the upland pastures for their livestock and when snow starts, they move down to the winter pastures, located in the valley’s bottoms and plain areas at lower elevation. Their way of life is shaped by the region’s harsh climate, rugged terrain, forage and water availability. Their subsistence is based on animal husbandry, supported by small-scale agriculture and trade with local stalled communities. Pastoralists maintain a strong connection to their cultural traditions, relying on communal practices and social networks to navigate the challenges of this environment, including access to grazing rights and the impacts of environmental change. Pastoralist’s mobility across different elevations in summer and winter pastures is critical, as it is a survival strategy and also balancing ecological balance, ensuring pastures sustainability and allowing pastoral areas to regenerate during off seasons.

Figure: Annual cycle of pastoralists between summer and winter pastures (Source: Muhammad Khurshid)

1.2.4 Socio-Cultural Features of Pastoral Societies

Pastoral societies have some well-established cultural features, these include the following:

First and foremost, these are cultures that revolve around herd animals. All aspects of culture are shaped by a preoccupation with herds. The size of a family’s herds is a measure of wealth and social status. Animals are used for meat, milk, blood, cloth, and leather. Animals are gifted to cement social relationships such as marriage and slaughtered to commemorate special occasions or the visit of an honored guest. Animals are passed down from fathers to children, establishing the social position and durability of families. Many pastoralist societies have vibrant traditions of music and oral poetry celebrating their animals and their herding lifestyle.

A second feature of pastoral societies is mobility. When herding is the primary livelihood, the group must constantly be on the move. Many agricultural societies also keep domestic animals, but in these cases, the people and their animals stay put on the farm, as crops are the fundamental means of survival. Therefore, farmers tend to have many fewer animals than herders. With larger herds feeding from what are often marginal lands, pastoralists must drive their animals to fresh pastures on a regular basis, often in seasonal cycles over large rangelands. The mobile life of herding groups is structured by various strategies of nomadism and transhumance. Mobility discourages the accumulation of private property other than herd animals, further enhancing the value of animals to herding groups.

Third, pastoralists rely on a division of labor based on gender and age. And the workload is heavy. Those living in pastoralist societies must herd animals to good pasture, provide them with water, search for new pastures, protect animals from predators, care for sick and weak animals, process animal products such as meat and milk, and produce or obtain all the other elements of material culture necessary for daily life. Day-to-day herding is often carried out by boys, while older men take on more complex tasks such as providing water from hard-to-access wells and hunting down predators. Older men also manage herds, buying and selling animals to optimize ratios of male to female, old to young. And men settle arguments and make family decisions about resources and security. Women are frequently responsible for milking animals, processing milk products such as cheese and yogurt, and selling those products in local markets. Women and girls make tents and mats, set up and break down camps, gather firewood and wild foods, and do the cooking. Women also care for sick animals and people, maintaining the store of knowledge about available plant medicines.

The fourth feature of herding societies is ecological knowledge related to animals and the environment. Pastoralists have developed an intimate understanding of the vegetation and water sources necessary for their herds as well as medicinal and edible plants available in different zones of their rangelands. They have deep insight into the anatomy and behavior of their herd animals. They know the qualities associated with different species and how to mix species by gender and age to maintain the availability of animal products such as milk, meat, and wool. Previously, scholars thought that pastoralism was destructive to the environment because of overgrazing. In recent decades, however, studies have demonstrated that herding groups strategically rotate their herds across their rangelands to control the impact on the environment, creating a sustainable way of life (Jennifer Hasty et al., 2022).

1.2.5 Key Challenges

Pastoralists have historically been a sustainable livelihood option. However, increased environmental stresses and changes in policies and practices, including restricting access to land and water, have increased the environmental impacts of pastoralism, including:

- Overuse of water resources:

- Access to water is a limiting factor when determining herd sizes for many individuals and communities, particularly in drylands.

- As such, there is a high risk that competition for water may lead to overuse. This is especially true when considering the additional water needs of wildlife.

- Overgrazing:

- Overgrazing can occur due to increased population and herd sizes and reduced land access due to degradation and conversion to other land uses.

- The impacts of overgrazing include loss of vegetative cover and associated soil erosion in the most extreme cases, with negative impacts on wild grassland species as well as inland waterways, which can suffer from sedimentation.

- Livestock – wildlife conflicts:

- Livestock–wildlife conflicts in pastoral systems can occur when livestock come into competition with other grazers for water and fodder.

- Conflict with other grazers tends to be most noticeable during periods of stress such as drought, when it is common for pastoralists to move herds into protected areas in search of water and fodder.

- Other challenges include the following

- Modernization

- Insecure land tenure

- Unsustainable pastoral resources development

- Socio-political marginalization

- Civil insecurity: Wars and violent conflicts

- Ecological consideration: conservation policies

- Climate change induced stresses (desertification, floods, land degradation etc.)

For detailed study please read this article Socio-political and ecological stresses on traditional pastoral systems: A review https://shorturl.at/r4hXx

Positive Environmental Impacts:

Despite the environmental challenges facing pastoralists, they have traditionally managed drylands sustainably and delivered a number of positive benefits for biodiversity. For example, in many cases, sustainable grazing practices actually increase species diversity and maintain ecosystem structures. Pastoralism can also contribute positively to the reduction of disasters such as fires, drought and flooding through the active management of vegetative cover.

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

Video on Afghan Kuchi nomads [A case study of Afghan Kuchi nomads]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwO6OunP7gg

References Cited:

Dong, S., Kassam, K.A.S., Tourrand, J.F. and Boone, R.B., 2016. Building resilience of

human-natural systems of pastoralism in the developing world. Edited by Shikui Dong, Karim-Aly S. Kassam, Jean François Tourrand and Randall B. Boone. Switzerland: Springer. http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/58253/1/84.pdf

Jennifer Hasty, David G. Lewis, Marjorie M. Snipes, (2022). Introduction to Anthropology

(Book). ISBN 13: 9781951693992.

Scanes, C.G., 2018. The neolithic revolution, animal domestication, and early forms of

animal agriculture. In Animals and human society (pp. 103-131). Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805247-1.00006-X

Singh, R. and Kerven, C., 2023. Pastoralism in South Asia: Contemporary stresses and

adaptations of Himalayan pastoralists. Pastoralism, 13(1), p.21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13570-023-00283-7

Ventresca Miller, A.R., Bragina, T.M., Abil, Y.A., Rulyova, M.M. and Makarewicz, C.A.,

2019. Pasture usage by ancient pastoralists in the northern Kazakh steppe informed by carbon and nitrogen isoscapes of contemporary floral biomes. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 11, pp.2151-2166. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-018-0660-4

Further Reading Material:

Jennifer Hasty, David G. Lewis, Marjorie M. Snipes, (2022). Introduction to Anthropology

(Book). ISBN 13: 9781951693992. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/1150

Little, M. A. (2015). Pastoralism. In Basics in Human Evolution (pp. 337-347). UK:

Academic Press.

Ventresca Miller, A. R., Bragina, T. M., Abil, Y. A., Rulyova, M. M., and Makarewicz, C.

A. (2019). Pasture usage by ancient pastoralists in the northern Kazakh steppe informed by carbon and nitrogen isoscapes of contemporary floral biomes. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 11: 2151-2166. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-018-0660-4