Unit 3.4: Improving Governance of Pastoral Lands

Instructor: Dr. Hasrat Arjjumend

Under this unit, we will focus on the need and prospects of improving a governance of rangelands and pastures. First, it is necessary to decode the important of mobility of pastoralists and their livestock. It is because we consider critical on priority the nomadic and semi-nomadic nobilities of the pastoral people. Accordingly, emphasizing the legislation and policy spaces for mobile pastoralists would be highlighted.

3.4.1 Importance of Mobility for Pastoral Land Governance

Mobility from one landscape to another herding the animals is essential part of nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralist lifestyles. It is inevitable strategy of the pastoral people to cope with the uncertainties of the weathers, availability of grazing resources, potential risks across the grazing routes, and many other factors affecting them and their livestock. Ian Scoones has highlighted many different types of mobility – from vertical migration from the summer to winter pastures in Amdo Tibet in China, to seasonal movement across the savannas of Kenya and Ethiopia, to the complex, changing transhumance patterns across Europe (in Sardinia, Spain or the Italian Alps), or Latin America (including Chile, Peru and Mexico). Scholars elaborated that pastoral mobility implies that pastoralists can move to areas with pasture for grazing of their livestock. Moreover, pastoral mobility means that the effect of unforeseen events, e.g. outbreak of disease, bush fire, locust attack, can be mitigated. Finally, migration between different agro-ecological zones means that more animals can be kept than in each of the zones (Niamir-Fuller 1998, Scoones 1995b). Through mobility pastoralists are able to produce animal-source products that provide food and income security to populations in the world’s rangelands. Such a practice also provides a range of benefits to the environment, while fostering the capacity to adapt to changing social and natural environments (FA, 2022).

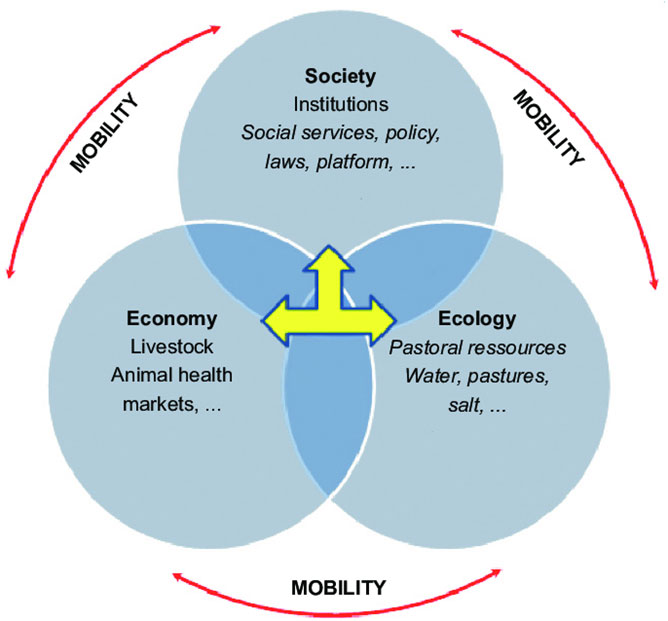

Photo: Three Pillars of Pastoral Mobility (Courtesy: Saverio Krätli)

Why is mobility important?

FAO book “Making way: developing national legal and policy frameworks for pastoral mobility” (FAO, 2022) precisely explains the importance of pastoral mobility. According to FAO, “Mobility lends pastoralism the adaptive capacity to optimize the variable environmental conditions that characterize more than half of the earth’s land surface. Not only is it crucial for the sustainability of pastoral livelihoods but also it benefits the environment in several ways. It provides food and livelihood security to millions of people in challenging terrains. Given the advantages of livestock mobility in both economic and environmental terms, the paramount role of mobile pastoralism in achievement of livestock-related Sustainable Development Goals is clear. The importance of pastoral mobility is now being recognized in development discourse. Local and international development organizations are beginning to advocate for policies that favour mobility.”

Livestock mobility plays a vital role in managing rangeland resources and optimizing livestock productivity in environments where rainfall and forage availability vary in both time and space. This mobility allows for the flexibility needed to adapt to scattered and unpredictable resources. Pastoralists strategically decide when and where to graze their animals, aiming to provide access to fodder at its nutritional peak, leading to greater productivity. The shared use of natural resources and the selection of breeds well-suited to local conditions further support this mobility. In some instances, pastoral mobility also reinforces trade networks, which are critical for broader economic development, extending beyond the livestock sector. Historically, pastoral migration routes have often aligned with trade routes, fostering mutual interest in maintaining these pathways. Additionally, livestock mobility contributes to landscape management and restoration, making it a valuable tool in the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030).

Thus, Livestock mobility is critical for improving rangeland governance, as it allows herders to manage grazing pressure and prevent land degradation. In ecosystems with unpredictable rainfall and forage distribution, moving livestock ensures that animals can access different grazing areas, reducing the strain on any one location. This practice supports the ecological balance of rangelands, helping to maintain soil fertility and biodiversity. Furthermore, mobility fosters cooperation among pastoral communities, enabling shared management of resources and promoting resilience in the face of environmental challenges. As a dynamic approach, it contributes to sustainable rangeland management and long-term productivity.

Task for Students

Share your thoughts about the necessity of pastoral and livestock mobility for the better management of rangelands and improving its governance at local level. Give your impression in Forum P-001.

Answers and Feedback of Students:

M3 Responses Students4

References Cited:

FAO (2022). Making way: developing national legal and policy frameworks for

pastoral mobility. FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines, No. 28. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8461en

Niamir-Fuller, M. (1998). The resilience of pastoral herding in Sahelian Africa. In:

Berkes, F., Folke, C. and Colding, J. (eds), Linking social and ecological systems: management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience, pp. 250-284. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scoones, I. (2023). Mobility is vital for successful pastoralism. Pastres. Blog.

https://pastres.org/2023/12/15/mobility-is-vital-for-successful-pastoralism/

Scoones, I. (1995). New Directions in Pastoral Development in Africa, pp.1-36. In:

Scoones, I. (ed), Living with uncertainty: new directions in pastoral development in Africa. Exeter: Intermediate Technology Publications.

3.4.2 Improving Legislation and Policies

Policies that support pastoral mobility are insufficient, and historically, they have often undermined and restricted mobility, viewing it as unproductive, outdated, irrational, and ecologically harmful (FAO, 2022). The first step in addressing this issue is to understand and analyze the existing legislation and policies in different countries. It is equally important to consider the plurality of legal systems and institutions in areas where customary, community-based, or religious laws and institutions influence pastoral practices and mobility.

Before discussing the legislation and policies at international, regional and national levels, let us watch the following video to understand the challenges.

Courtesy: YouTube

The above video hints that there are not only the difficulties in coping with geoclimatic, topographic and other natural problems faced by the mobile pastoralists, but political, economic and policy environments are hostile to these vulnerable people and their animals. One such good example is highlighted in the box below.

Box: Overlaps and contradictions in Swedish laws affecting the Sami

Following a vote in favour for the UNDRIP in 2007, the Swedish Constitution explicitly recognized the Sámi as a “people” on 1 January 2011 (UN Human Rights Council, 2011), stating that “opportunities of the Sámi people and ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities to preserve and develop a cultural and social life of their own shall be promoted”. Mobile reindeer pastoralism is central to the Sámi community’s social and cultural life, but land rights and the mobile use of land were considered as being exhaustively regulated under the prevailing reindeer herding legislation (Mörkenstam, 2019). The 1971 Reindeer Grazing Act recognizes the Sámi’s right to use land and water for themselves and their reindeer within certain geographic areas defined by the law. Reindeer herding rights in Sweden are exclusive to Sámi and are limited to those Sámi who live within designated communities within Sweden. They exclude Sámi from neighbouring countries such as Norway and Finland whose traditional routes may pass through Swedish territory (Anders Utsi, personal communication, October 2021). Thus, the law controls Samí mobility through its control of access to resources despite the need for more flexibility in resource use.

While in line with the UNDRIP, Swedish law recognizes in principle that Sámi land use can result in ownership rights to land, and there are still significant difficulties in realizing such rights (UN Human Rights Council, 2011), indicating the need for better integration of laws across departments, scales and modes.

International Instruments Supporting Mobile Pastoralists

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights: It is highly relevant to pastoralists, particularly in guaranteeing the right to freedom of movement and residence within a country’s borders, as well as the right to leave and return to one’s country (Article 13). Additionally, it ensures the right to social security and the realization of economic, social, and cultural rights (Article 22). For pastoralist communities, these rights are exercised through the practice of pastoralism and mobility. Therefore, any restrictions on pastoralist practices constitute a violation of these fundamental rights (FAO, 2022).

- Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (ILO Convention 169): It obligates states, under Article 14, to take appropriate measures to protect the right of indigenous peoples to use lands they do not exclusively occupy but have traditionally accessed for subsistence and cultural activities, with special consideration for nomadic peoples (FAO, 2022). The convention also requires governments to “take appropriate measures, including through international agreements, to facilitate contacts and cooperation between indigenous and tribal peoples across borders, including in economic, social, cultural, spiritual, and environmental fields” (Article 32). Additionally, Article 33 mandates that states propose legislative and other measures to implement the provisions of the convention (FAO, 2022).

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP): In Article 20, UNDRIP reaffirms the collective rights essential for the existence, well-being, and holistic development of indigenous peoples. It asserts their right to securely enjoy their own means of subsistence and development, as well as to freely engage in all traditional and other economic activities (FAO, 2022).

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP): Adopted in 2018, UNDROP mandates states to take legislative, administrative and other appropriate steps to ensure respect, protection and fulfilment of the rights set out in the declaration (FAO, 2022).

- UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: According to FAO (2022), it included the seasonal droving of livestock along migratory routes in the Mediterranean and the Alps in its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2019, following applications by Austria, Greece, and Italy. Such recognition obligates states to invest in and preserve this heritage. It can also have a catalytic effect: for instance, in Spain, Act 10/2015 requires the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage, and transhumance was officially added under Royal Decree 385/2017 (FAO, 2022). Should similar efforts be replicated in other countries where mobile pastoralists continue to preserve this heritage?

- Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries, and Forests in the Context of National Food Security: This provide guidance on improving governance of pastoral lands through Technical Guide No. 6. This guide offers insights into how the voluntary guidelines can be applied in pastoral settings and identifies key action areas for integrating them into national tenure governance frameworks, ensuring their effective implementation (FAO, 2022).

Regional Instrumental Supporting Transhumance and Pastoralism

- The Policy Framework for Pastoralism in Africa: Introduced in 2011, it offers guidance and promotes the development of pro-pastoral policies by African Union Member States. Among its eight core principles is the recognition of strategic mobility as vital for efficient rangeland use, protection, and climate change adaptation. It emphasizes the need for supportive land tenure policies, legislation, and regional policies that facilitate cross-border movements and livestock trade (FAO, 2022). The framework advocates for policy support for mobility both within and between countries, ensuring inclusive processes that foster dialogue and active participation of both pastoralists and non-pastoralists.

- ECOWAS Decision on the Regulation of Transhumance between Member States: It was established to allow the free movement of livestock across borders within the region. Transhumance is permitted upon the issuance of an ECOWAS International Transhumance Certificate, which details the herd's composition, vaccinations, planned route, border crossings, and final destination (FAO, 2022). While the decision was innovative in its provisions and impact, its implementation has faced challenges, as regional agreements rely on national policies and laws for enforcement. Recent regulations enacted by some ECOWAS Member States have diverged from the decision's intent, undermining its effective implementation (FAO, 2022; Krätli and Toulmin, 2020).

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Transhumance Protocol: Approved in early 2020 for its eight Member States in eastern Africa, it is modelled after the ECOWAS International Transhumance Certificate. It commits Member States to harmonize legislation and policies related to livestock, pastoral practices, animal health, and land use to ensure effective implementation. The protocol's implementation is coordinated and monitored by ministers responsible for livestock and pastoral development in each Member State, with technical support provided by the IGAD Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development (FAO, 2022).

- European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): CAP provides guidelines for supporting and improving agriculture, with detailed implementation frameworks established at the country level, following the principle of subsidiarity. Regulation No. 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and Council sets rules for direct payments to farmers and pastoralists under CAP support schemes. Additionally, Commission Decision No. 2010/300/EU amended Decision No. 2001/672/EC regarding time periods for the movement of bovine animals to summer grazing areas (FAO, 2022).

In addition, numerous bilateral agreements on pastoral mobility have been signed between countries. While the level of detail varies, these agreements typically address key provisions such as eligibility (who and what are covered), spatial coverage (the geographical areas to which the agreement applies), required documentation, the timing of transhumance (when and for how long), control and enforcement measures, the institutional framework (including relevant laws and regulations) for coordinating implementation, and mechanisms for dispute resolution (FAO, 2022).

National and Sub-National Laws and Policies

- Indian Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act of 2006: Ministry of Tribal Affairs of India recognized the right of forest dwelling communities, including mobile pastoralists, to land and other resources. Accordingly, the law was enacted and some people have got benefits.

- Stock Route Management Act of Queensland, Australia (2002): This law provides the legal framework for overseeing the network of stock routes and reserves used for moving livestock across the state. The Act outlines principles for managing this network, including the planning and monitoring of livestock movements, while clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders. It mandates the creation of a state-level stock route network management strategy, with the day-to-day management responsibilities devolved to local governments, in accordance with specific stock route network management plans (FAO, 2022).

- Spain's Law on Cattle Trails (1995): It highlights the social and environmental significance of seasonal livestock migration. It acknowledges that the cattle trail network is essential to the extensive livestock production system, enabling the productive use of "underused grazable resources" (FAO, 2022). The law mandates that cattle trails primarily serve to facilitate livestock movement, restricting other uses to those that are compatible with or complementary to this purpose. In addition to recognizing transhumance as intangible cultural heritage, some regional governments provide financial support for transhumance on the hoof, offering subsidies of EUR 4 per day per livestock unit (Government of Extremadura, 2019) or EUR 9 per head per livestock unit for the entire route (Comunidad Foral de Navarra, 2019).

- Morocco's Law on Transhumance and Rangeland Management (2016): The law outlines the principles and institutional framework for the sustainable management of rangelands and pastoral mobility. It ensures pastoralists' rights to access and use rangelands and their resources, while also providing mechanisms for resolving disputes that may arise during transhumance (FAO, 2022). The law establishes a national commission responsible for planning, designating, and managing transhumance corridors, working in collaboration with regional committees in each pastoral region. According to Article 24, herders must obtain authorization (autorisation de transhumance pastorale) from the relevant authority to engage in transhumance. This authorization includes information on the herd owner, the composition of the herd by number and species, its place of origin, the intended route, destination, and the period and duration of the authorization (FAO, 2022).

- The Pastoral Code of Niger (2010): The Code affirms that mobility is a fundamental right of pastoralists, recognized and protected by both the state and local governments. It emphasizes that mobility is a rational and sustainable way to utilize pastoral resources. The Code specifies that pastoral mobility can only be temporarily restricted for reasons related to the safety of people, animals, forests, or crops, and only under conditions defined by law. Developing local-scale policies is often effective due to the diversity of pastoral systems within the country, offering opportunities to create contextually appropriate tools for safeguarding mobility that complement national legislation (FAO, 2022).

- Law No. 3016 of the Province of Neuquén, Argentina (2016): Such a law guarantees pastoralist families and their livestock the right to move between summer and winter grazing areas, recognizing this mobility as essential for environmental conservation and the preservation of the region's natural and cultural heritage. The law mandates that livestock migration corridors be used primarily for pastoral mobility, prohibiting any uses that are non-complementary or incompatible. It also establishes a commission responsible for managing the network of corridors and ensuring the law’s implementation (FAO, 2022).

Students are advised to read the following laws given in the box below.

Box: List of National Laws Supporting Pastoralism

- Act 3/1995 of 23 March on Cattle Trails (Spain)

- Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 1994

- Decree for Implementation of the Pastoral Charter (Mali)

- Decision A/DEC.5/10/98 of ECOWAS relating to the Regulations on Transhumance between ECOWAS Member States (1998)

- Law No. 3016 of 30 September 2016 (Neuquén Province, Argentina)

- Law on Pastures (Kyrgyz Republic)

- Law on Pastures, 2013 (Tajikistan)

- Law Relating to Pastoralism, 2002 (Burkina Faso)

- Law on Transhumance and Rangeland Management, 2016 (Morocco)

- Ordinance Relating to Pastoralism, 2010 (the Niger)

- Pastoral Charter, 2001 (Mali)

- Pastoral Code, 2000 (Mauritania)

- Pastoral Code, 2010 (the Niger)

- Rural Land Administration and Use Proclamation, 2009 (Afar National Regional State, Ethiopia)

- Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 (India)

- Stock Routes Management Act, 2002 (Queensland, Australia)

Comunidad Foral de Navarra. 2019. Resolución 411/2019, de 17 de abril, del Director

General de Desarrollo Rural, Agricultura y Ganadería, por la que se establecen las bases reguladoras para la concesión de ayudas a la trashumancia a pie, acogidas al régimen de minimis, y se aprueba la convocatoria de ayudas para el año 2019. Boletín Oficial de Navarra, 92: 5901–5904. https://bon.navarra.es/es/anuncio/-/texto/2019/92/6/.

FAO (2022). Making way: developing national legal and policy frameworks for

pastoral mobility. FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines, No. 28. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8461en

Kratli, S. and Toulmin, C. (2020). Farmer–Herder Conflict in sub-Saharan Africa? A

working paper for AFD. London: IIED.

Morkenstam, U. (2019). Organised hypocrisy? The implementation of the

international indigenous rights regime in Sweden. International Journal of Human Rights, 23(10): 1718–1741.

UN Human Rights Council. 2011. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of

indigenous peoples. Addendum: The situation of the Sámi people in the Sápmi region of Norway, Sweden and Finland, 6 June 2011, A/HRC/18/35/Add.2.