Unit 2.6: Climate Resilient or Vulnerable? A Pastoralism Paradox

Instructor: Dr. Evan F. Griffith

Learning Objectives:

- Describe the six vulnerability pathways of pastoralists, including the exposures, sensitivities, and adaptations associated with each.

- Apply a vulnerability pathway to the Turkana County case study

- Understand what resilience means in the pastoralism context

- Define the main features of climate resilience among pastoralists

- Analyze a case study of increased camel adoption in East Africa

- Apply lessons from pastoralism resilience to other contexts

2.6.1. Vulnerability and Resilience

Climate Change, caused by the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes, is a global emergency that has led to more frequent and intense extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, and droughts (IPCC, 2022). Paradoxically, pastoralists are suffering from some of the most severe impacts of climate change, although resilience to climate variability is at the core of pastoralism (Krätli, 2022). For example, the longest drought in 40 years struck East Africa from 2020-2022, killing 3.6 million livestock in Kenya and Ethiopia, and one-third of livestock in Somalia (FAO, 2022). By the end of 2022, 20 million people in the region faced high acute food insecurity, with over 2 million at emergency food insecurity levels (FAO, 2022).

This raises two key questions:

- What community-based solutions and policies are needed to support pastoralist climate resilience?

- What lessons do pastoral systems offer to the rest of the world in the face of climate change?

The COP28 Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action plays a critical role in the global conversation around building sustainable agricultural systems in the face of climate change. For pastoralists, this declaration is highly relevant as it addresses the urgent need to adapt food systems to increasing climate variability while ensuring the resilience of communities that depend on natural resources. Pastoralism, a system deeply rooted in mobility and communal resource management, faces unique challenges that intersect with the global goals outlined in the COP28 Declaration. As pastoralists are among the most vulnerable to climate change, yet also demonstrate remarkable resilience, the policies discussed in the declaration can either support or undermine their traditional practices and livelihoods.

Before diving into this unit’s discussion, review the COP28 Declaration to consider how global climate action frameworks may help or hinder pastoralist resilience. This will set the stage for critically engaging with the questions surrounding pastoralism and climate resilience.

Task for Students to Post in Forum P-001

- Read the COP28 Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action: https://www.cop28.com/en/food-and-agriculture

- Answer the question in your post: Do you think this declaration helps or hurts pastoralists? Why?

Answers and Feedback of Students:

M2 Responses Students6

Vulnerability to Climate Change

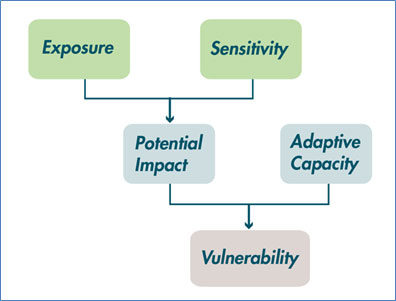

Figure 1: Key components of climate vulnerability (Glick et al., 2011).

The long-term viability of pastoralism in light of climate change has been a continuous theme for discussion since the mid-2000s. Some argue that pastoralism cannot continue due to its internal incapacity to deal with climate change, while others trace climate vulnerability to socioeconomic marginalization and external factors.

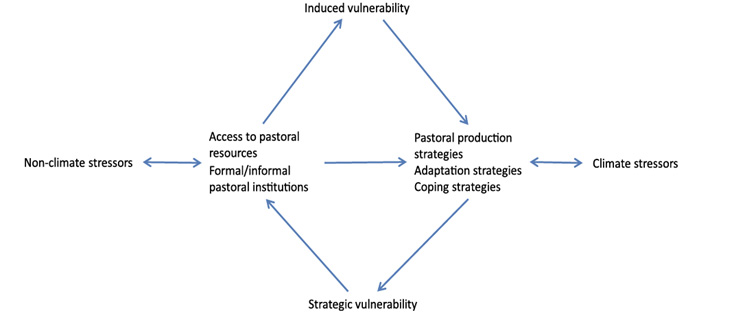

A climate vulnerability framework is helpful for examining the climate and non-climate transformations affecting pastoralists. Vulnerability is influenced by exposure to these transformations, the sensitivity of pastoral resources to their impacts, and adaptive capacity—the ability to minimize risks or benefit from changes (see Figure 1).

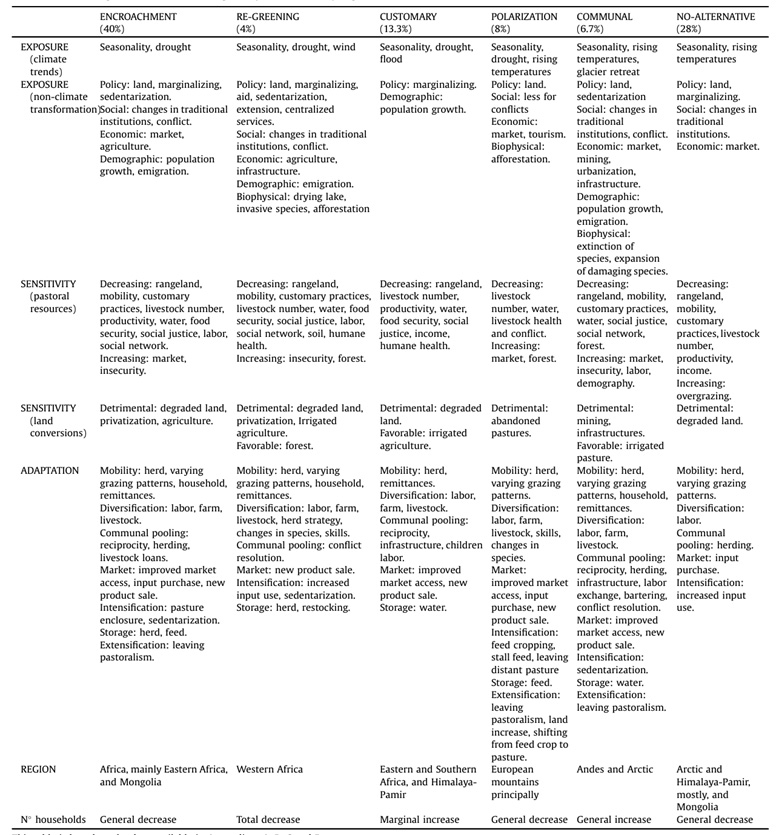

In the pastoral context, climate exposures include changing seasonality of precipitation, drought, rising temperatures, floods, and less snow. Non-climate exposures include ill-conceived policies marginalizing pastoralism, changing traditional institutions such as the dismissal of elder’s councils, violent conflicts, increased marketization, encroachment of agriculture on pastoral lands, population growth, and forest and shrub expansion, although this last factor can also be linked to climate change (see Prosopis example from the previous section) (López-i-Gelats et al., 2016; Semplici and Rodgers, 2023).

In terms of sensitivity, i.e., impacts on pastoral livelihoods, decreased access to rangelands, growing difficulties in moving and conducting customary management practices, decreased size and health of herds, and increased access to markets are associated with climate and non-climate transformations (López-i-Gelats et al., 2016).

Common adaptation strategies include herd mobility and changing grazing patterns, the combination of pastoralism with other economic activities, reciprocal social relations, communal planning and herding, increased trade and market access, pasture enclosure, herd accumulation, abandonment of pastoralism, and government/NGO aid (Nassef, 2023).

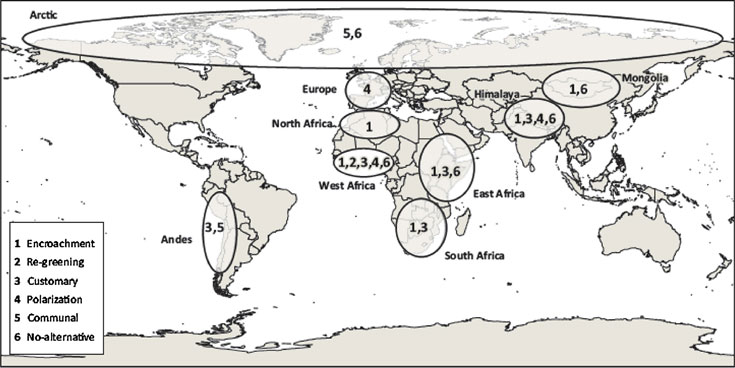

A meta-analysis of sensitivity pathways highlights how pastoralists around the work are responding to these transformations (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Location of vulnerability pathways from each case study (López-i-Gelats et al., 2016).

Next, I briefly describe each one of the pathways and their defining characteristics.

Consider while you read: Can you think of examples of these vulnerability pathways in your own country and context? What are the climate and non-climate exposures, impact on access to pastoral resources, and adaptation strategies in your example?

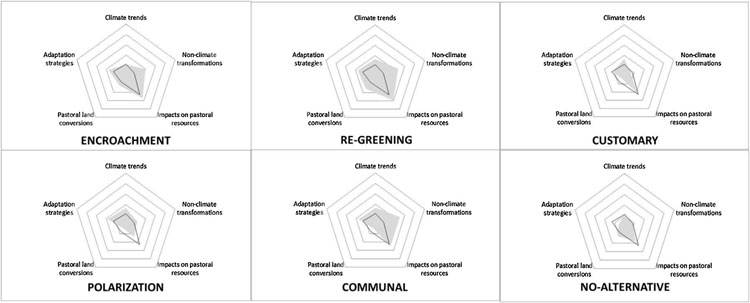

Vulnerability Pathways (López-i-Gelats et al., 2016).

- Encroachment, distinguished by the loss of control of pastoral land in a context of persistent unfavorable development policies and declining operationalization of pastoral production strategies and institutions. Land privatization, the expansion of agriculture, mining, and urbanization contribute to the encroachment on rangelands, reducing access to critical resources such as land, water, and social networks.

- Re-greening, distinguished by afforestation in a context of acute non-climate transformation and declining access to pastoral resources, to which pastoral communities mainly respond through emigration and diversification. These shifts are mainly seen in the West African Sahel. While afforestation provides pastoralists with additional fodder and forest products, the non-climate transformations have an overall negative impact on pastoral livelihoods.

- Customary, distinguished by the larger preservation of pastoral production strategies and institutions and minor exposure to non-climate transformations, specifically those dealing with land, mobility, and agriculture. Found mainly in Eastern and Southern Africa, the main adaptation strategy is diversification in the allocation of family labor, farming activities, and type of livestock raised. Access to water and rangelands is still decreasing, and increased food insecurity and poor human health are reported.

- Polarization, distinguished by the shifting towards ranching, through the concentration of the pastoral production strategies where conditions enable the adoption of intensive rearing and abandoning the rest of the land. It predominantly occurs in mountainous regions in Europe, and is characterized by increased tourism industry, market integration, and shrub and forest encroachment.

- Communal, distinguished by the great aptitude for adaptation to major non-climate transformations through communal pooling. Found in regions like the Andes and Arctic, pastoralists in this pathway struggle with species extinction, population growth, and land degradation. However, communal pooling of resources and labor exchange systems help pastoralists adapt to challenges while maintaining some traditional practices.

- No-alternative, distinguished by the lack of economic options other than pastoralism in a context of increased input use in the pastoral activity. In regions such as the Arctic and parts of Mongolia, pastoralists have increasingly limited mobility and productivity, often intensifying livestock management to cope. However, the pathway offers little room for adaptive strategies, leading to a significant decline in the pastoral way of life.

Figure 3: Performance in the main components of the vulnerability of pastoralism of the diverse pathways. The scores of the figures are percentages, going from 0 in the centers to 100 in the extremes. Out of the total of items of the five components of the three dimensions of vulnerability reported considering all case studies of our sample, the percentage indicates the number of them that were reported in each pathway of vulnerability. The average scores are in black, while the scores specific for each pathway are in grey (López-i-Gelats et al., 201).

Vulnerability Pathway Case Study: Oil Exploration in Turkana County, Kenya

Source: Lind, 2018

Task for Students

Read the following article: https://pastres.org/2018/11/16/when-pastoralism-meets-oil-learning-from-oil-finds-in-turkana-kenya/

Watch the following videos:

Based on above article and video, fill in the following table based on the reading and videos:

| Exposure (climate trends) | |

| Exposure (non-climate trends) | |

| Pastoral resources (decreasing or increasing) | |

| Land conversions (detrimental or favorable) | |

| Adaptations |

Share or upload your table in Forum P-001.

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

The four major influences on climate vulnerability among pastoralists, according to López-i-Gelats et al. (2016) include:

- Double exposure from climate and non-climate vulnerabilities:

- Unfavorable development policies that marginalize pastoral groups and prioritize other land uses;

- Viability of adaptation strategies;

- And the multifaceted role of markets.

The paradox we identified at the beginning of the unit – namely that climate resilience is inherent to pastoralism, but pastoralists are some of the most vulnerable communities in the face of climate change – can be understood by examining these pathways, in which non-climate transformations exceed the climate transformations. It is not simply climate change itself, but the combination of droughts, floods, and other hazards with policy, sociocultural, economic, and ecological drivers (e.g., encroachment, ecological degradation, weakening of traditional systems of resource management and reciprocity, and economic stratification) that explains the increased vulnerability of pastoral groups to climate variations (Krätli et al., 2022; López-i-Gelats et al., 2016). As Osman (2018) says: “It is not drought that makes pastoralists vulnerable, but their growing inability to cope with it.”

Table: Commonalities and specificities of the vulnerability pathways (López-i-Gelats et al., 2016).

Pastoralist adaptation strategies, explored in more detail in the next section, include mobility, diversification, communal pooling, market, storage, and intensification practices. However, it is important to note that some of these mechanisms are coping strategies (i.e., short-term and transient in nature) or a normal part of pastoralism, which is a flexible livelihood strategy. Coping strategies may provide immediate relief during environmental, economic, or social shocks, but they often do not offer long-term solutions to structural vulnerabilities (e.g., failed cash crop ventures). Sustainable adaptation strategies, which go beyond coping mechanisms, require systemic changes in governance, infrastructure, and support systems to ensure the resilience of pastoralist communities in the face of ongoing challenges such as climate change, resource competition, and economic pressures.

Pastoralists are increasingly integrated into global markets, which can provide opportunities for trade and economic diversification. However, this integration often creates dependency on market conditions that pastoralists cannot control, making them vulnerable to market fluctuations (e.g., food and livestock prices during a drought). Economic stratification can also occur with market integration, with wealthier households can afford better inputs (veterinary, fodder, etc.) and poor ones can’t sustain their herds.

There are two aspects of vulnerability that are important to consider. First is the vulnerability inherent to using natural resources in any livelihood (i.e., strategic vulnerability). Managing this type of vulnerability is inherent to pastoralism and suggests that pastoralists hold important lessons for dealing with climate variability and extremes for the rest of the world. The other type of vulnerability comes from non-climate drivers, like political marginalization and encroachment on pastoral resources (i.e., induced vulnerability).

Figure 4: Diagram showing how induced and strategic vulnerability influence pastoralism within the context of climate and non-climate factors (López-i-Gelats et al., 2016).

Thus, building climate resilience among pastoralists requires enabling policies and recognizing pastoral rights and institutions. In particular, multi-level governance structures ensure that decisions affecting pastoralists—ranging from local resource management to national policy—are made inclusively, accounting for the perspectives and needs of pastoralists at various levels. By involving communities in the decision-making process, governance structures can become more adaptive and responsive to both climatic and non-climatic stressors.

Community-based management practices should also be embraced, leveraging the traditional ecological knowledge and social networks that pastoralists have developed over generations. These practices, described in the previous section, allow pastoralists to manage their resources and adapt to environmental changes collectively. When combined with support from government policies and external resources, these community-based approaches can lead to sustainable adaptation strategies, reducing vulnerabilities and fostering resilience against climate change, land encroachment, and economic pressures.

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

2.6.2. Lessons from Pastoralists in Climate Resilience

Resilience is the other side of vulnerability. First, we will define resilience and describe its characteristics among pastoralists. Then, we will examine a case study of how herd composition is a key resilience strategy in East Africa. Finally, we will explore what lessons pastoralism holds for the rest of the world regarding uncertainty, increased climate variation, and extremes.

Definition: Resilience refers to the ability of systems, entities, or communities to anticipate, adapt, and recover from shocks while maintaining their core functions and structures. Initially rooted in ecology, engineering, and psychology, the concept has expanded to encompass various disciplines, including development and climate change.

In this domain, resilience is proposed as a theory and practice to slow down the runaway climate process by changing social and economic practices (Folke et al., 2010). Critics highlight that resilience in these spaces focuses on managing the effects of poverty and vulnerability by enabling and capacity building rather than eradicating them, contributing to the problem of resource depletion (Chandler, 2020).

Nonetheless, in the context of climate change and development, resilience is seen as a key framework for enabling pastoralist communities, especially those in vulnerable regions like East Africa's drylands, to cope with and thrive amidst environmental and socio-economic stresses (Semplici & Campbell, 2023).

A key aspect of climate resilience among pastoralists is the influence of non-equilibrium ecosystems.

Task for Students:

Watch the following video:

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

We’ve explored climate vulnerability, but now I will ask a different question: What can we learn from pastoralists who are forging a livelihood in ecological and politically variable contexts?

Key elements of pastoral livelihood systems that enhance their resilience to variability and uncertainty include mobility, effective herd management (such as herd composition, size, and strategic splitting), robust social networks, local ecological knowledge, adaptive practices, and sustainable resource utilization (Semplici & Campbell, 2023). Of course, these have been highlighted in previous units in this module (e.g., the logic of mobility, traditional ecological knowledge, and others). I will briefly summarize some of these key aspects below to emphasize how they contribute to climate resilience and what lessons we can learn from these strategies.

Mobility: Mobility is inherent to pastoralism through the logic of natural resource access. Turner & Schlecht (2019) highlight two types of mobility: 1) grazing mobility, which refers to the daily movement of livestock around a base location (e.g., camps, villages, water points), and 2) travel mobility, which involves the movement of livestock herds between different base locations (e.g., seasonal transhumance). In the face of changing seasonal precipitation due to climate change, mobility is a key to accessing resources that may be available at unpredictable times.

Herd Management: As we covered in the previous unit, herd composition and splitting are strategies that rely on traditional ecological knowledge of fodder and environmental conditions to take advantage of availability of grass and browsing resources. In northern Kenya and Uganda, and southern Ethiopia, droughts are becoming more common and frequent. As a result, camel herding is increasing due to their resistance to drought (Megersa et al., 2024; Volpato et al., 2019; and Watson et al., 2016).

Social Networks: These networks foster relationships and processes that enable communities to adapt to and navigate uncertainties and variability through resource sharing and support, knowledge transmission (e.g., TEK, market engagements, and early climate warning mechanisms), emotional and moral support, and negotiation and exchange (e.g., with farmers and market actors). They also include communal land tenure systems that support resource sharing and mobility (Semplici et al., 2024).

Traditional ecological knowledge: This was covered extensively in the previous unit. TEK allows pastoralists to thrive in arid and semi-arid environments based on their intimate knowledge of biota, ecosystems, and practices.

Adaptive Practices: As we explored in the previous section on vulnerability, pastoralists continuously innovate and adapt their practices, such as changing crop choices, integrating new technologies, and integrating with markets.

Sustainable Resource Use: Pastoralists engage with the environment differently from ‘modernity.’ Importantly, pastoralism is a low-input livestock production system that does not require large fossil fuel inputs. Thus, it can manage variability without speeding up the process of arrival at the earth’s planetary boundaries (e.g., CO2 emissions).

Task for Students

Watch from minute 4 to 50 of this STanD Lecture:

(Dr. Greta Semplici)

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

Regenerative Grazing Case Study:

A recent movement in the United States, called regenerative grazing is taking off.

Task for Students: Watch the documentary below.

Soil Carbon Cowboys documentary:

Mandatory Quiz: [Click Here]

More Carbon Cowboy films: https://carboncowboys.org/films-top/films

2.6.3. Conclusion

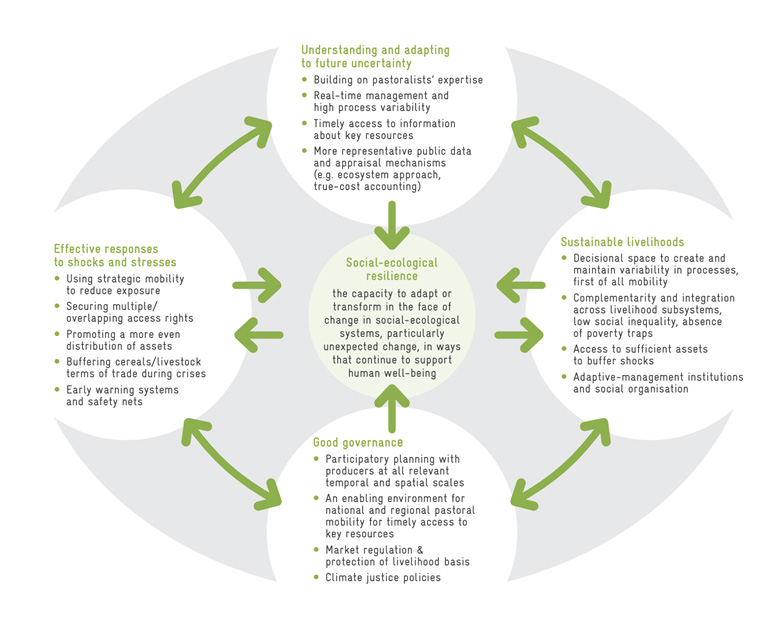

Figure 5: A social-ecological resilience framework based on pastoral systems (Krätli et al., 2023).

As we’ve covered, various factors contribute to pastoralists’ resilience in the face of climate change, including factors inherent to pastoralism. The key takeaways include (Krätli et al., 2023):

- Variability and flexibility – pastoralists embed variability in their livelihood processes, which allows them to adapt quickly to changing conditions. These include strategic mobility to take advantage of grazing and economic opportunities. This is perhaps particularly important given the rise in xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment around the world in recent years. Migration and mobility should be supported as a key adaptation strategy for communities.

- Integration with nature – Pastoralists thrive in rangelands by working with nature, especially in nonequilibrium ecosystems that require flexibility, rather than separate from it, based on their traditional ecological knowledge. As a result, pastoralist systems require low fossil fuel inputs and are highly adaptable to unpredictable environments. Capitalist and modern economies can learn something from pastoralists and work within the planetary bounds (Steffen et al., 2015).

- Diversity of assets – Pastoralists maintain diverse assets, including livestock species, and extensive social networks, which help them buffer against individual hazards. While assets of livelihoods systems vary, asset diversification as a fundamental principle can be supported (e.g., even in financial investment, this is a key principle). Moreover, investment in social institutions and networks (e.g., traditional governance systems of natural resources) needs to be a key aspect of climate change adaptation.

Pastoralism is an inherently resilient livelihood system in the face of increased climate variability, yet pastoralists are still considered the most vulnerable to its effects. Addressing the underlying social and economic issues (e.g., ill-conceived policies, loss of traditional institutions, conflict, impact of markets, and encroachment of agriculture on pastoral lands) is needed.

References Cited:

COP28 UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and

Climate Action (COP28 UAE, 2023). https://www.cop28.com/en/food-and-agriculture

Glick, P., Stein, B. A., & Edelson, N. A. (2011). Scanning the conservation

horizon: a guide to climate change vulnerability assessment. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation. 168 p. https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/37406

IPCC, 2022: Summary for Policymakers [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, A. Reisinger, R.

Slade, R. Fradera, M. Pathak, A. Al Khourdajie, M. Belkacemi, R. van Diemen, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, D. McCollum, S. Some, P. Vyas, (eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.001.

Krätli, S., Lottie, C., Mikulcak, F., Foerch, W., & Feldt, T. (2022). Pastoralism

and resilience of food production in the face of climate change. https://www.giz.de/de/downloads/giz2022-en-technical-background-paper-climate-resilience-and-pastoralism.pdf

Lind, J. (2018, November 16). When pastoralism meets oil: Learning from oil

finds in Turkana, Kenya. PASTRES. https://www.pastres.org/2018/11/16/when-pastoralism-meets-oil-learning-from-oil-finds-in-turkana-kenya/

Megersa, B., Temesgen, W., Amenu, K., Asfaw, W., Gizaw, S., Yussuf, B. and

Knight-Jones, T. 2024. Camels in Ethiopia: An overview of demography, productivity, socio-economic value and diseases. ILRI Research Report 121. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/149289

Nassef, M. (2023). Pastoralism and Climate in African Drylands. United States

Agency for International Development (USAID), Feinstein International Center, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/Pastoralism-and-Climate-in-African-Drylands.pdf

Osman, A. M. K., Olesambu, E., & Balfroid, C. (2018). Pastoralism in Africa's

drylands: reducing risks, addressing vulnerability and enhancing resilience. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330882153_Pastoralism_in_Africa's_drylands_Reducing_risks_addressing_vulnerability_and_enhancing_resilience

Roe, E. (2020). A new policy narrative for pastoralism? Pastoralists as reliability

professionals and pastoralist systems as infrastructure. In STEPS Working Paper 113. Brighton: steps Centre. https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=wp-content/uploads/2020/01/STEPS-working-paper-113-Roe-FINAL-for-opendocs.pdf

Semplici, G., & Campbell, T. (2023) The revival of the drylands: relearning

resilience to climate change from pastoral livelihoods in East Africa, Climate and Development, 15:9, 779-792. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2022.2160197

Semplici, G., & Rodgers, C. (2023). Sedentism as doxa: Biases against mobile

peoples in law, policy and practice. Nomadic Peoples, 27(2), 155-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.3197/np.2023.270201

Semplici, G., Haider, L. J., Unks, R., Mohamed, T. S., Simula, G., Tsering, P., ...

& Taye, M. (2024). Relational resiliences: reflections from pastoralism across the world. Ecosystems and People, 20(1), 2396928. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2024.2396928

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E.

M., ... & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. science, 347(6223), 1259855. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1259855

Watson, E. E., Kochore, H. H., & Dabasso, B. H. (2016). Camels and climate

resilience: adaptation in northern Kenya. Human Ecology, 44(6), 701-713. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-016-9858-1

Further Reading:

Suvdantsetseg, B., Kherlenbayar, B., Nominbolor, K., Altanbagana, M., Yan, W.,

Okuro, T., ... & Zhao, X. (2020). Assessment of pastoral vulnerability and its impacts on socio-economy of herding community and formulation of adaptation options. APN Science Bulletin. https://www.apn-gcr.org/publication/assessment-of-pastoral-vulnerability-and-its-impacts-on-socio-economy-of-herding-community-and-formulation-of-adaptation-options/

Marty, E., Bullock, R., Cashmore, M., Crane, T., & Eriksen, S. (2023). Adapting

to climate change among transitioning Maasai pastoralists in southern Kenya: an intersectional analysis of differentiated abilities to benefit from diversification processes. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 50(1), 136-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2121918

Zeren, G., Tan, J., Zhang, Q., & Qiuying, B. (2023). Rebuilding rural community

cooperative institutions and their role in herder adaptation to climate change. Climate Policy, 23(4), 522-537. https://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/tcpoxx/v23y2023i4p522-537.html

Baker, D. (2023). Climate change and transboundary risks in African rangelands.

https://cgspace.cgiar.org/items/7075dbdf-fd53-4076-a1d1-c5381717726e

Köhler-Rollefson, I. (2023). Hoofprints on the land: how traditional herding and

grazing can restore the soil and bring animal agriculture back in balance with the earth. Chelsea Green Publishing. https://shorturl.at/StRfw

Gillin, K., & Turner, M. D. (2022). Book review of Pastoralism–Making

Variability Work by Saverio Krätli and Ilse Koehler-Rollefson and a discussion of the inherent challenges of writing about pastoralists at the global scale. https://pastoralismjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13570-021-00222-4

Carbon Cowboys literature:

https://carboncowboys.org/amp-grazing-research/published-research